Back to School

Think you're doing everything you can to obtain maximum transfer efficiency? Think again. The University of Northern Iowa’s Spray Technique Analysis & Research (STAR) program proves that transfer efficiency isn’t as much about the gun as it is the person holding it...

#workforcedevelopment #pollutioncontrol

For Rick Klein, the key to maximizing transfer efficiency in manual liquid spray paint operations isn’t necessarily about the latest and greatest spray gun or the newest nozzle designs to come along. While he doesn’t dispute that technology can play an important role, he believes the single most important factor is not the gun. “It’s all about the technique,” he says.

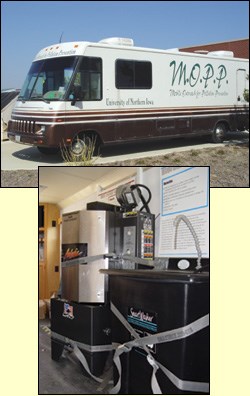

Klein should know. As the senior research technician at the University of Northern Iowa’s (UNI) Waste Reduction Center (IWRC) in Cedar Falls—a sort of free consulting agency devoted to assisting small businesses with environmental regulations and cost-saving measures—he heads up the agency’s Spray Technique Analysis & Research (STAR®) program, a training course designed to improve efficiency of manual spray painting operations.

Featured Content

A STAR is Born

The idea for STAR originated in 1993, when IWRC received a grant to examine the impact of spray technician training on material consumption and air emissions during the automobile refinishing process. Using donated equipment and coatings—and using 24 volunteer painters from the collision repair industry as test subjects—the research team monitored the painters’ transfer efficiency both before and after they participated in a training seminar. What they discovered was that regardless of the equipment that the painter used, transfer efficiency improved dramatically following the training course.

The entire experiment might have ended there, had the volunteer painters not gone back to their job shops singing the praises of the training program to their bosses and co-workers. Before long, the auto body shop owners—intrigued by the prospect of material savings—were asking if they too could participate in the study. When the IWRC obliged and the owners saw the impact that the training had on their own performance, they began asking if they could send the rest of their staffs in for training.

By 1996, news of the research program had spread from the auto body refinishing community into industrial finishing job shops and plants. At the same time, instructors from community colleges and vocational schools were inquiring as to how they might be able to get involved. In order to deal with all of the interest being generated, the IWRC sought and received the funding necessary to turn the one-time research study into a full-time training course…and STAR was born.

Without enough staff members to accommodate the swelling interest in the program, the team decided to focus its efforts on establishing additional training sites—primarily on the campuses of community colleges—both in and outside of Iowa and certifying instructors to head-up the instruction at the satellite locations. At the same time, a STAR certification system was developed to differentiate between classroom only training, hands-on instruction and endorsement to conduct STAR training.

The STAR program’s “train the trainer” approach has paid off tremendously. To date, there are 33 training sites in 18 states—including seven sites in Iowa, five in California and four in Hawaii—and dozens of certified instructors (see Figure 1 for complete list of states with STAR training sites). Klein estimates that more than 2,500 students have participated in IWRC's painting programs.

A typical STAR training session begins with a pre-test in which the student is videotaped as he or she paints a part. The paint gun and the part are each weighed before and after the test, which allows the team to calculate overspray, VOC emissions and transfer efficiency.

| Figure 1: States With STAR Training Sites | |

| California | Missouri |

| Connecticut | Montana |

| Florida | Nebraska |

| Hawaii | Nevada |

| Illinois | Pennsylvania |

| Indiana | Rhode Island |

| Iowa | Texas |

| Kansas | Virginia |

Once the pre-test has been completed, both student and instructor review the video footage of the student’s “performance” and look for flaws in technique. Klein says that a lot of the mistakes he sees on video are fairly common. “A lot of painters flip their wrist at the end of a stroke,” he says. “That’s fine if you are blending layers, but otherwise, it's not something that should be happening.” He also says that novice technicians tend to spray as if they were painting with a brush, another big no-no. “There are a lot of would-be Michelangelos out there,” he laughs. Other common mistakes include holding the gun too close or too far from its target, inadvertent rotation of the gun as the technician sweeps along a part and improper gun and nozzle set-up.

After the video analysis, the instructor introduces the student to alternative spray techniques. One of the primary tools used in this part of the training is the LaserTouch® Targeting Tool. Invented by Klein, the LaserTouch can be mounted on to any model spray gun. Two laser beams project from the tool to the target painting surface. The laser beams can be adjusted to form a single dot when the spray gun is at the correct pre-set distance from the part. If the gun moves too far or too close, the beams separate. This enables the operator to paint and maintain the correct distance for consistent coverage. The single dot can also be used to target the spray pattern on the part that results in an accurate 50% overlap on the painting surface. If the painter strays from the proper spray distance or angle, two separate laser images will appear on the part alerting the spray technician to the inconsistent spraying.

During the training session, the instructor also reviews other variables affecting spray efficiency, such as gun setup, mixture content and maintenance practices. “It's amazing how many students discover that their [efficiency] problems are the result of their refusal to take the time to maintain their guns or learn how to use them properly in the first place,” says Chris Lampe, one of the STAR instructors. At the end of the training session, the student participates in a final spraying session, where he or she applies what they’ve learned that day. Overspray, VOC emissions and transfer efficiency are then recalculated and compared to pre-training results. On average, students see a 22% increase in transfer efficiency and a corresponding decrease in materials cost (see Figure 2 for complete table).

STAR Trek

250 miles down the road from IWRC, Steven Youngs is speaking to a dozen or so students in the auto body shop at Northwest Iowa Community College (NCC). Youngs, who heads the school’s Automotive Body & Service Technology program, is also a certified STAR instructor.

As part of the Auto Body curriculum at NCC, students are required to take two automotive refinishing courses. Youngs has integrated the STAR training program into the classes in an effort to reach his students before they develop bad painting habits. He says that it is also an opportunity to educate the students on the importance of some of the financial and environmental issues they will have to deal with in their careers. “Somebody who understands that transfer efficiency is a means for reducing material costs and emissions is a more desirable job candidate in the eyes of most prospective employers,” he says.

| Figure 2: Average Improvement of STAR Trainees During the Past Year | |

| Yearly $$$ savings ...............................................................$6,497 Average increase in transfer efficiency ........................................27% Average decrease in materials cost (gallons of coating) ................22% Average decrease in pounds of VOCs/year ..................................22% Average decrease in actual pounds of VOCs .............................285lbs |

|

Youngs first got involved with the STAR program a couple of years ago, when NCC’s Trade & Technology Dean told him about its existence and suggested that he look into it. “I went out to UNI and participated in the ‘train the trainer’ program,” he says. “A couple of weeks later, the STAR team came out here and provided us with the materials we needed.” Klein and his colleagues visit about twice a year to service the equipment and make sure everything is working properly.

Although Youngs has integrated the STAR program into his students' refinishing courses, the shop also serves as a satellite training site for industrial finishers. Nemschoff Chairs, with a manufacturing facility in nearby Sioux Center, regularly sends employees over to Youngs for training. Whereas his college students will be introduced to various aspects of the STAR training over the course of a year, outside industrial finishing students are exposed to a day’s worth of intensive one-on-one training. Customers like Nemschoff typically pay a small fee for the training, which generates revenue for the Auto Body program.

Youngs and other STAR trainers have access to an online database maintained by IWRC. Once a student has completed the training, the instructor enters the pre- and post-training results into the database. The database allows Klein and his colleagues to monitor performance on the basis of training site, state or region or for the trainees collectively. It also provides them with the ability to view average efficiencies for particular gun types. To date, more than 500 pre- and post-test results have been entered into the database.

Back in Cedar Falls, Klein is discussing the need for more industry training. While industries like welding and metal cutting often demand that the workers have some type of formal training, the need for proper paint training is often taken for granted. “A lot of people have told us that, a day before, they were a janitor or maybe a welder,” he says. “And then one day, the painter doesn’t show up and the shop manager tells you ‘you’re the painter now.’ There’s absolutely no training whatsoever.”

The good news is that, thanks to programs like STAR, that approach is becoming a thing of the past. By proving that a quality finish, material cost savings and emissions control are inextricably linked, Klein and his colleagues are sending a powerful message to shop owners and managers everywhere—paint training is not an option, it’s a necessity.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Back to School in Switch to Powder Coating

School furnishings manufacturer Fleetwood Group makes the change from liquid coating and learns a valuable lesson.

-

How a Generation Lost So Many Employability Skills

Before the next generation of advanced manufacturing talent comes of age, perhaps parents need to ask themselves whether overparenting is part of the employability skills problem.

-

Reinvigorating the Workforce

Do education and outreach hold the key to solving manufacturing’s workforce problem?