Michael Burbey and Chris French admit they are probably not a supplier’s ideal customer when it comes to their finishing operation at GE Transportation’s manufacturing plant in Erie, Pennsylvania.

“We are probably the worst customer to have because of our demands,” says Burbey, a senior manager of manufacturing engineering for the plant, which makes locomotives for passenger and freight trains.

Featured Content

“We’re very difficult to deal with,” adds French, a senior manufacturing manager.

GE Transportation spent more than $6 million to install an electrocoating line in the facility in 2017, which included adding a sophisticated pretreatment system that the managers say has helped truly revolutionize the way the company operates.

“We say our manufacturing operation is the three D’s: dangerous, difficult and dirty,” Burbey says. “And our finishing side had always been dangerous and dirty, so getting a new ecoat line helps me get the paint gun out of our people’s hands. We can reduce guys with 7-inch grinders from having to work dangerously on these welds, and I can also now get to places that we could never paint by hand. So, has it changed and improved us? Oh, yes.”

The company says it builds the world’s most comprehensive and competitive locomotive portfolio that reduces operating costs and fuel usage, minimizes downtime and complies with stringent emissions standards.

Adding the ecoat line was a four-year venture by Burbey and French that culminated last year in a new line that has made just about every operation at Building 7 in the Erie plant perform better.

Addressing a Finishing Bottleneck

A few of the parts GE manufactures for its locomotives can be as wide as 6 feet, and some of the components have as many as 200 smaller parts that need to be coated, so the complexity of the finishing operation needed to be addressed in order for the plant to operate more efficiently.

“Finishing was a bottleneck,” Burbey says. “We had a pretreatment spray washer system from 1983, and we couldn’t move parts through fast enough. It was way past its prime, and we knew something had to change. But it just took time to get things going. When it did, we wanted to make it worth it.”

Hence their difficult-customer label, which they carried in the planning, building and opening of the ecoat line and the pretreatment operation. They wanted the new system to hum.

“It was a dated, tired system, and we wanted to get a line in here that truly spoke performance and efficiency,” French says. “The plan was to drop the new line into the same footprint, so everything involved very precise engineering and making sure we made the right decisions on suppliers and vendors. With the money we spent, it had to work right from the beginning.”

The coated parts processed on the line are assembled to make up GE locomotives, which cost roughly $2.5 million each and weigh almost 300,000 pounds. The huge 4,500-horsepower locomotives are built in Lawrence Park, just outside of Erie, and represent a phenomenal technological advancement over engines built as early as 20 years ago, the company says.

For one, they are much cleaner engines, producing more than 90 percent less particulate matter and oxides of nitrogen (NOx), a major component of smog and ozone, than locomotives produced 15 years ago. This reduction is accomplished through GE’s Exhaust Gas Recirculation (EGR) system, which takes a portion of the exhaust gas and cools it before rerouting it back to the engine-charged air. And because the specific heat capacities of the exhaust gas components are higher than that of air, the result is a reduced combustion temperature and less NOx formation.

An Old, Tired System

To get the project started, Burbey and French went to GE management in 2013 and explained that the plant’s wet-spray coating system with a four-stage iron phosphate line had to go, and a new system with more eco-friendly chemicals and systems needed to take its place.

“It was a tired system, way past its prime,” Burbey says. “We also had a powder booth and a manual wash station for hand-washing parts, and also some older ovens. It all just had to go.”

Burbey and French visited several other manufacturing operations outside of GE to see how they coated parts and came away with some very specific ideas. The challenge was getting the right equipment and dropping it into the same footprint, a feat that is easier said than done. The goal was to be able to apply two types of ecoat paint: a cathodic epoxy and a cathodic acrylic. About 90 percent of the parts processed through the new line would need ecoat; the rest would receive a wet or powder coating.

The first step before approaching GE management stemmed from a joke between Burbey and French: They each updated their resumes before making the big push for the equipment.

“It was going to be a lengthy process to get approval, and many different things can happen,” French says. “We kidded about our resumes, but that actually was the first step. Then we made our case to management.”

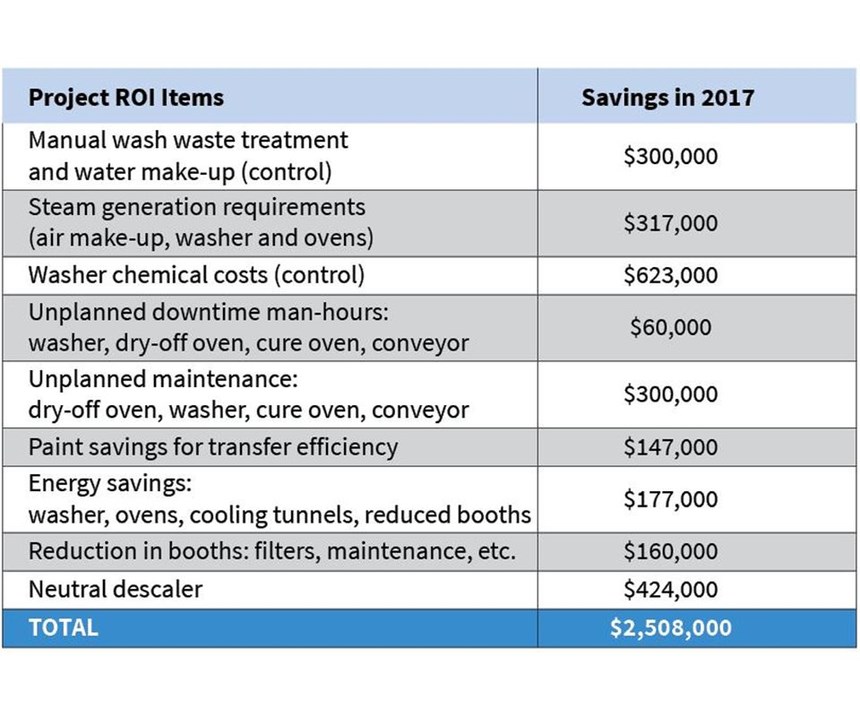

French knew he wanted a chemical pretreatment process that was probably a seven-stage system. Burbey was planning for a two-color line, and from there they started putting together budget numbers. They assembled what GE internally calls a “4-Blocker,” a return-on-investment chart that shows how the company can make investment money back in cost savings.

Solving Safety Issues

One aspect of that potential cost savings covered safety issues, too. GE’s locomotive manufacturing process involved many people grinding heavily scaled welds and laser cuts, smoothing surfaces so that any coating would adhere properly. That grinding and buffing was the source of most of the on-the-job injuries at the plant, as debris and small bits of grinding materials would fly through the air and sometimes get into workers’ eyes.

“That was one of the things we were looking to do away with,” Burbey says of the grinding. “We wanted a pretreatment line that could also descale the material and rid us of having to grind as much as we did. This was definitely a cost factor.”

In the fall of 2014, GE management gave Burbey and French the go-ahead to begin planning the project, and the two men set out to discuss options with suppliers and vendors, a task they say earned them that difficult-customer reputation.

GE quickly placed an order with Therma-Tron-X for the Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, company’s highly regarded Sliderail Square Transfer system, the backbone for the ecoat line. From that point on, French focused on the equipment side of the ecoat line while Burbey oversaw the chemistry side, which included a validation testing process for the pretreatment system. At the same time, they laid out the scope of work for paint testing so they could determine which ecoat supplier they would use.

In early 2016, deconstruction of parts of the GE facility began, as the planning went from paper drawings to dismantling and moving around older equipment to get ready for the new pretreatment system and ecoat equipment. That July, the new equipment began arriving and was installed. Simultaneously, Burbey was working with GE engineers to spec the new ecoat process, test out vendors and get an independent lab to verify results.

A New Zirconium System

Atotech USA, a specialty chemicals manufacturer with North American headquarters in Rock Hill, South Carolina, was chosen to supply the pretreatment chemicals. Atotech already had a strong relationship with GE through its Texas manufacturing plant, so the chemical supplier was very familiar with GE’s needs and requirements.

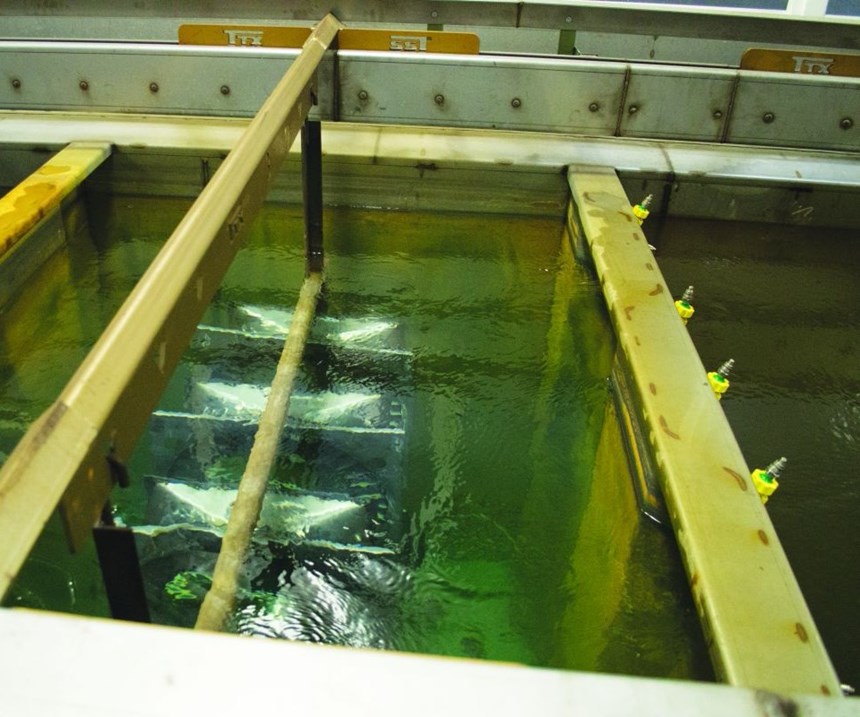

Burbey wanted a seven-stage zirconium system that would help get the parts ready for ecoat, as well as descale and reduce the sludge from the old iron phosphate system the Erie facility had in place for decades.

“Atotech was a known process to us since 2013 in Texas, and our engineers were very comfortable with what they had been doing for us,” Burbey says. “But it wasn’t a shoe-in for them. We brought in five different chemical suppliers to see what everybody had, but we were happy with Atotech’s results.”

Still, Atotech dedicated a group of employees to the GE project to ensure it delivered the same results in Pennsylvania as it had in Texas. The supplier had already qualified its Interlox line of zirconium-based paint pretreatment processes with GE at the Erie plant in 2012, but GE had decided to install the different chemical process in Texas instead. The requirement there was for a phosphorus-free system that passed a 1,000-hour salt-spray test.

Steve Raynor, Atotech’s product marketing manager, led extensive testing for the new GE project, and his team determined that Interlox 5707 was the ideal product for this application. Interlox 5707 is a phosphorus-free zirconium pretreatment process designed to provide paint adhesion and corrosion resistance on a variety of metal substrates, including steel, galvanized steel, aluminum, zinc and magnesium.

“We were working with GE back in 2009 when they first started moving most of the finishing operations to non-phosphate technology,” Raynor says. “We knew what they fully expected from us.”

He says the primary advantage of Interlox 5707, besides being phosphorous-free, is that it offers stable performance across a wide range of operating conditions, as well as automated replenishment capabilities, which simplifies process operation. In addition, it is free of heavy metals such as chrome, nickel and zinc, and is suitable for both spray and immersion applications. It also produces minimal sludge compared to conventional phosphate pretreatments and can be operated at ambient temperatures.

Adding a Neutral Descaler

Early last year, Burbey also tasked Atotech with providing a chemical descaling alternative to help reduce the amount of grinding needed to remove weld and laser-cut scale from the locomotive components prior to painting. One of the primary requirements for any such product was a near-neutral pH to minimize etching and to meet GE’s waste-treatment requirements. Atotech’s Stephen Taylor and Paul Butkovsky went to work on that part of the overall GE project, collaborating with Atotech scientists and researchers in Rock Hill. They were able to develop a solution, despite the fact that GE gave them a list of prohibited components that “was about the size of a small phone book,” Raynor says with a chuckle.

“GE had a lot of waste-treatment concerns, safety needs, and overall general health and safety issues, and that gave us a real tight box to work in,” he says. “But we were able to identify a solution, and everything proved out well to GE’s satisfaction.”

With the support of its global R&D group, Atotech developed UniPrep ACD 105, a low-acidity weld descaler that operates at near-neutral pH in immersion applications. The process also supports improved electrophoretic paint coverage and paint adhesion on welded and heat-affected zones. UniPrep has no hard chelators and is said to be very easy on waste-treatment systems.

With this request to add a chemical descaler, GE took on the challenge of switching the planned seven-stage system to a nine-stage system midway through the installation process, at a cost of about $60,000 for the change.

“We spent a little bit more money up front, but it was well worth it to get the descaler in, because our eye injuries have gone down,” French says.

In addition to coming up with the descaling solution and the pretreatment chemistry for the new line, Atotech hosted all potential ecoat vendors at its South Carolina research facility to help GE determine which company would supply the ecoat for the system. The company set up lines so each vendor could process parts per GE’s engineering specs. Burbey oversaw the entire process in person to ensure that all testing and results met GE’s standards. Once the results were in, GE selected a coating from Valspar, which is now a part of Sherwin-Williams. Natalie Caratelli-Fox, business development manager for Sherwin-Williams, says Vectrogard epoxy and V-Shield acrylic technologies are in use at GE.

Both Burbey and French are ecstatic with how the four-year process of putting in a newer system has turned out.

“At the end of the day, we needed to have a locomotive that we can turn over to our customers that can be a showpiece,” Burbey says. “When you have a locomotive rolling down the tracks and little Johnnie is watching a Union Pacific with an American flag go by, then it better look good.”

For information, visit getransportation.com, ttxinc.com, atotech.com, valsparindustrial.com and cchemco.com.

RELATED CONTENT

-

8 Things You Need to Know About Paint Booth Lighting

Global Finishing Solutions has come up with some helpful insights on lighting for paints booths which plays a crucial role in achieving a quality paint job.

-

Coating Systems with the Best Long-Term Performance

The best protection against corrosion and UV exposure, says Axalta’s Mike Withers, is electrocoat and a super durable powder coating.

-

Wireless Carrier Fleet Provides Modular Overhead Conveyance

Wireless, modular conveyor system provides flexibility and scalability for carrying parts through finishing processes.