Electro-codeposition of MCrAlY Coatings for Advanced Gas Turbine Applications - 12th Quarterly Research Report

The aim of this research is to seek a sulfur-free plating solution for electro-codeposition of (Ni,Co)-CrAlY composite coatings. In this quarter, the coating plated in the sulfur-free, all-chloride plating solution with sodium lauryl sulfate wetting agent showed the best oxidation performance. This coating also demonstrated much better oxidation resistance that the bare CMSX-4 alloy.

#nasf #aerospace

by

Prof. Ying Zhang* & B.L. Bates

Featured Content

Department of Mechanical Engineering

Tennessee Technological University

Cookeville, Tennessee, USA

Editor’s Note: This NASF-AESF Foundation research project report covers the twelfth and final quarter of project work (October-December 2020) on an AESF Foundation Research project at the Tennessee Technological University, Cookeville, Tennessee. A printable PDF version of this report is available by clicking HERE.

Summary

MCrAlY coatings electrodeposited in a Watts bath typically contain a trace amount of sulfur, which can adversely affect their high-temperature oxidation resistance. Sulfur-free, all-chloride plating solutions were utilized in the electro-codeposition process to lower the sulfur content in the Ni-Co coating matrix. Three solutions were prepared. One solution included no wetting agent, while the other two solutions contained sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) and Triton X-100 (TX100), respectively. After plating, the NiCo-CrAlY composite coatings were heat treated at 1080°C in vacuum and were converted to the NiCoCrAlY coatings that consisted of phases such as γ-(Ni,Co), β-NiAl, etc. The cyclic oxidation resistance of the coatings plated in the all-chloride solutions were evaluated in air at 1100°C for 200 hr (1-hr per cycle with a total of 200 cycles). The coating plated in the solution with SLS wetting agent showed the best oxidation performance. This coating also demonstrated much better oxidation resistance that the bare CMSX-4 alloy. The results suggest that the all-chloride solution can be used to reduce the sulfur content in the MCrAlY coatings and satisfactory oxidation performance could be achieved. Further evaluation is needed to elucidate the effects of wetting agent on both the coating quality and oxidation behavior.

Technical report

I. Introduction

To improve high-temperature oxidation and corrosion resistance of critical superalloy components in gas turbine engines, metallic coatings such as diffusion aluminides or MCrAlY overlays (where M = Ni, Co or Ni+Co) have been employed, which form a protective oxide scale during service.1 The state-of-the-art techniques for depositing MCrAlY coatings include electron beam-physical vapor deposition (EB-PVD) and thermal spray processes.1 Despite the flexibility they permit, these techniques remain line-of-sight which can be a real drawback for depositing coatings on complex-shaped components. Further, high costs are involved with of the EB-PVD process.2 Several alternative methods of making MCrAlY coatings have been reported in the literature, among which electro-codeposition appears to be a more promising coating process.

Electrolytic codeposition (also called “composite electroplating”) is a process in which fine powders dispersed in an electroplating solution are codeposited with the metal onto the cathode (specimen) to form a multiphase composite coating.3,4 The process for fabrication of MCrAlY coatings involves two steps. In the first step, pre-alloyed particles containing elements such as chromium, aluminum and yttrium are codeposited with the metal matrix of nickel, cobalt or (Ni,Co) to form a (Ni,Co)-CrAlY composite coating. In the second step, a diffusion heat treatment is applied to convert the composite coating to the desired MCrAlY coating microstructure with multiple phases of β-NiAl, γ-Ni, etc.5

Compared to conventional electroplating, electro-codeposition is a more complicated process because of the particle involvement in metal deposition. It is generally believed that five consecutive steps are engaged:3,4 (i) formation of charged particles due to ions and surfactants adsorbed on particle surface, (ii) physical transport of particles through a convection layer, (iii) diffusion through a hydrodynamic boundary layer, (iv) migration through an electrical double layer and (v) adsorption at the cathode where the particles are entrapped within the metal deposit. The quality of the electro-codeposited coatings depends upon many interrelated parameters, including the type of electrolyte, current density, pH, concentration of particles in the plating solution (particle loading), particle characteristics (composition, surface charge, shape, size), hydrodynamics inside the electroplating cell, cathode (specimen) position and post-deposition heat treatment, if necessary.3-6

There are several factors that can significantly affect the oxidation and corrosion performance of the electrodeposited MCrAlY coatings, including: (i) the volume percentage of the CrAlY powder in the as-deposited composite coating, (ii) the CrAlY particle size/distribution and (iii) the sulfur level introduced into the coating from the electroplating solution. This three-year project aims to optimize the electro-codeposition process for improved oxidation/corrosion performance of the MCrAlY coatings. The three main tasks are as follows:

- Task 1 (Year 1): Effects of current density and particle loading on CrAlY particle incorporation.

- Task 2 (Year 2): Effect of CrAlY particle size on CrAlY particle incorporation.

- Task 3 (Year 3): Effect of electroplating solution on the coating sulfur level.

II. Background

A typical MCrAlY coating consists of 8–12% Al, 18–22% Cr, and up to 0.5% Y (in wt%). Other more complicated compositions of MCrAlYs contain additional elements such as hafnium, silicon and tantalum.7,8 The concentrations of some minor elements (e.g., sulfur, yttrium and hafnium) play an important role in affecting the growth and adhesion of the oxide scale. The detrimental effect of sulfur on oxide scale adherence of MCrAlY alloys has been well documented.9 Small amounts of sulfur can segregate to the alumina-metal interface and weaken the interface.10

The electrolytes used to deposit the nickel or cobalt metal matrix for forming the MCrAlY coating are typically sulfate- or sulfamate-based solutions.11,12 Approximately 0.006-0.013 wt% (60-130 ppm) of sulfur has been reported in electroplated nickel coatings using these solutions.13,14 Table 1 lists the five commercial nickel plating solutions and their deposition parameters.15 According to our previous study results, the fluoborate bath is not suitable for codeposition of CrAlY-based particles, due to the reaction between the solution and the powder at 50°C, leading to the formation of a dark powdery coating. The all-chloride solution appeared more promising. In this study, the oxidation performance of the MCrAlY coatings electrodeposited in the all-chloride solution was evaluated.

III. Experimental Procedure

The substrate material used in this study was Ni-based superalloy CMSX-4 (60.7 Ni-5.9 Al-6.3 Cr-9.6 Co-6.5 W-0.6 Mo-2.9 Re-6.5 Ta-1.0 Ti, in wt%, and 1100 Hf-17 C-1 S in ppmw). Disc specimens (1.6 mm thick, ~17 mm in diameter) were ground to #600 grit using SiC grinding papers, followed by grit blasting with #220 Al2O3 grit. The spherical CrAlY powder used in this research was manufactured via gas atomization by Sandvik. The powder had a mean particle diameter of 9.5 μm and it was sieved through a 20-μm screen (625 mesh) prior to usage.

Figure 1 - Schematic of the barrel system.

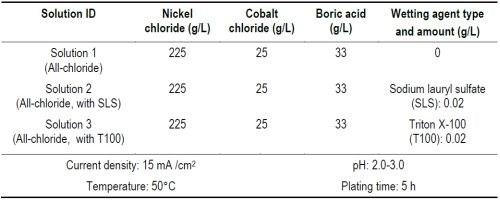

A rotating barrel system similar to the one illustrated in Fig. 1 was used in the electro-codeposition experiments.6 Three all-chloride solutions were prepared. Their compositions and the electro-codeposition parameters are given in Table 1. Two types of wetting agents were utilized. The sulfur-containing wetting agent was sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), and the sulfur-free one was Triton X-100 (T100).16

Table 1 - Composition of all-chloride solutions and plating conditions.

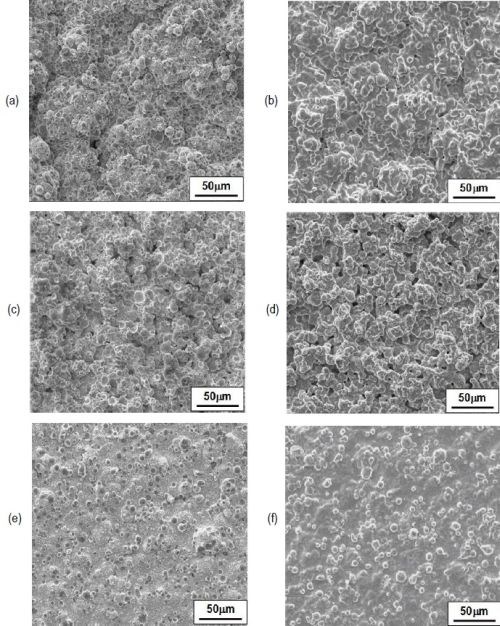

After plating, the coated specimens were heat-treated in vacuum for 6 hr at 1080°C. The purpose of the heat treatment was to convert the as-deposited Ni/Co-CrAlY composite coating to the NiCoCrAlY coatings that consisted of phases such as γ-(Ni,Co), β-NiAl, etc. The post-deposition heat treatment was carried out in a horizontal alumina tube furnace. A vacuum of at least 10-6 torr was maintained. The heating rate was 20°C/min. After completion, the samples were furnace cooled to room temperature. The coatings were examined by optical microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) equipped with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS)(Fig. 2).

Figure 2 - SEM surface images of the specimens for oxidation tests before and after heat treatment: (a) and (b): sample plated in the all-chloride solution (Coating #1, without wetting agent); (c) and (d): sample plated in the all-chloride solution with SLS wetting agent (Coating #2); (e) and (f): sample plated in the all-chloride solution with TX100 wetting agent (Coating #3).

The oxidation performance of the MCrAlY coatings was evaluated in cyclic oxidation testing at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL). The test was carried out in laboratory air with 1-hr cycles at 1100°C with a 10-minute cooling period. The specimens were removed and weighed every 20 cycles for the first 100 hours and every 50 cycles thereafter. The mass changes (±0.02 mg/cm2 accuracy) were recorded.

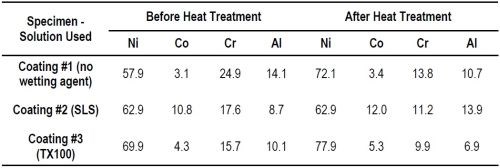

The coating surface compositions determined by EDS before and after heat treatment are summarized in Table 2. For all three coatings, a decrease in Cr content was observed, as a result of Cr evaporation in vacuum at 1080°C, similar to what was reported for MCrAlY coatings made by thermal spraying and EB-PVD.17,18

Table 2 - Coating surface compositions before and after heat treatment, as determined by EDS (wt%).

Coating #2 (plated in the solution with SLS) had higher Co, Cr and Al levels. Coating #1 (plated in the solution without wetting agent) had acceptable levels of Cr and Al, whereas the Co content was the lowest (i.e., 3.4 wt%). This was possibly due to a lower cathode efficiency, since there was no wetting agent in this solution and the specimen was plated at a lower pH value. The Co, Cr and Al levels were lower for Coating #3 (plated in the solution with T100). This was likely due to a lower particle incorporation in the coating.

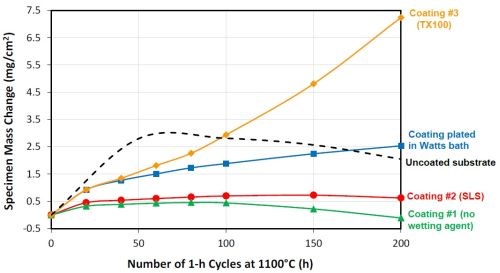

The specific mass changes after 200 1-hr cycles are presented in Fig. 3. The uncoated CMSX-4 substrate and a previous coating plated in the Watts bath were also included for comparison. A coating with good oxidation resistance should have a slow and steady growth in weight, due to the formation of a thin and adherent Al2O3 scale on the surface. Coating #1 had a slow steady mass gain in the first 100 cycles, but started to lose weight after 100 hr, indicating spallation of the oxide scale. Coating #3 (T100), on the other hand, showed a very rapid mass gain, as a result of fast growth of the oxide scale. Coating #2 (SLS) had the best oxidation performance, exhibiting a steady mass gain and only started to show signs of mass loss near the end of the 200-hr test. This coating also demonstrated much better oxidation resistance than the bare CMSX-4 alloy and exhibited lower weight gain than the coating plated in the Watts bath. In addition, the oxidation results were in good agreement with the coating surface composition.

Figure 3 – Specimen mass changes during 1-hr cyclic oxidation in laboratory air at 1100°C.

The current oxidation results suggest that with the proper wetting agent, the all-chloride solution can be used to reduce the sulfur content in the MCrAlY coatings and satisfactory oxidation performance could be achieved. Further evaluation is needed to elucidate the effects of wetting agent on both coating quality and oxidation behavior.

References

1. G.W. Goward, Surf. Coat. Technol., 108-109, 73-79 (1998).

2. A. Feuerstein, et al., J. Therm. Spray Technol., 17 (2), 199-213 (2008).

3. C.T.J. Low, R.G.A. Wills and F.C. Walsh, Surf. Coat. Technol., 201 (1-2), 371-383 (2006).

4. F.C. Walsh and C. Ponce de Leon, Trans. Inst. Metal Fin., 92 (2), 83-98 (2014).

5. Y. Zhang, JOM, 67 (11), 2599-2607 (2015).

6. B.L. Bates, J.C. Witman and Y. Zhang, Mater. Manuf. Process, 31 (9), 1232-1237 (2016).

7. J.R. Nicholls, MRS Bull., 28 (9), 659-670 (2003).

8. A.V. Put, D. Oquab and E. Péré, et al., Oxid. Met., 75 (5-6), 247-279 (2011).

9. J.L. Smialek, JOM, 52 (1), 22-25 (2000).

10. B.A. Pint, Oxid. Met., 45 (1-2), 1-37 (1996).

11. G.A. Di Bari, in Modern Electroplating, 5th Ed., Edited by M. Schlesinger and M. Paunovic, John Wiley & Sons, 2010; pp. 79-114.

12. R. Oriňáková, et al., J. Appl. Electrochem., 36 (9), 957-972 (2006).

13. R. Brugger, in Nickel Plating, 1st Ed., Clare O’Molesey Ltd., Molesey, Surrey, 1970; pp. 46-47.

14. H.M. Heiling, Metall., 14, 549-561 (1960).

15. N.V. Parthasaradhy, Practical Electroplating Handbook, Prentice Hall, 1989, p. 184.

16. S. Devaraj and N. Munichandraiah, J. Electrochem. Soc., 154 (10), A901-A909 (2007).

17. T.J. Nijdam, et al., Oxid. Met., 64 (5-6), 355-377 (2005).

18. I. Keller, et al., Surf. & Coat. Technol., 215, 24-29 (2013).

Past project reports

1. Quarter 1 (January-March 2018): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 82 (12), 13 (September 2018); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF18Sep1.

2. Quarter 2 (April-June 2018): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 83 (1), 13 (October 2018); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF18Oct1.

3. Quarter 3 (July-September 2018): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 83 (3), 15 (December 2018); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF18Dec1.

4. Quarter 4 (October-December 2018): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 83 (7), 11 (April 2019); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF19Apr1.

5. Quarter 5 (January-March): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 83 (10), 11 (July 2019); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF19Jul1.

6. Quarter 6 (April-June): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 84 (1), 17 (October 2019); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF19Oct2.

7. Quarter 7 (July-September): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 84 (3), 16 (December 2019); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF19Dec1.

8. Quarter 8 (October-December): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 84 (6), 11 (March 2020); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF20Mar3.

9. Quarter 9 (January-March): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 84 (9), 9 (June 2020); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF20Jun2.

10. Quarter 10 (April-June): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 85 (1), 15 (October 2020); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF20Oct1.

11. Quarter 11 (July-September): Summary: NASF Report in Products Finishing; NASF Surface Technology White Papers, 85 (4), 14 (January 2021); Full paper: http://short.pfonline.com/NASF21Jan2.

About the authors

Dr. Ying Zhang is Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Tennessee Technological University, in Cookeville, Tennessee. She holds a B.S. in Physical Metallurgy from Yanshan University (China)(1990), an M.S. in Materials Science and Engineering from Shanghai University (China)(1993) and a Ph.D. in Materials Science and Engineering from the University of Tennessee (Knoxville, Tennessee)(1998). Her research interests are related to high-temperature protective coatings for gas turbine engine applications; materials synthesis via chemical vapor deposition, pack cementation and electrodeposition, and high-temperature oxidation and corrosion. She is the author of numerous papers in materials science and has mentored several Graduate and Post-Graduate scholars.

Mr. Brian L. Bates is a R&D Engineer in the Center for Manufacturing Research at Tennessee Technological University, in Cookeville, Tennessee. He holds B.S. (2002) and M.S. (2010) degrees in Mechanical Engineering from Tennessee Technological University. Mr. Bates also worked at Alcoa-Howmet Corporation (Morristown, Tennessee) and in the Alloy Behavior & Design group at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Mr. Bates has been actively involved in many research projects on coating fabrication and evaluation.

*Corresponding author:

Dr. Ying Zhang, Professor

Department of Mechanical Engineering

Tennessee Technological University

Cookeville, TN 38505-0001

Tel: (931) 372-3265

Fax: (931) 372-6340

Email: yzhang@tntech.edu

RELATED CONTENT

-

A Process for Alkaline Non-cyanide Silver Plating for Direct Plating on Copper, Copper Alloys and Nickel Without a Silver Strike Bath

Traditionally, silver is electroplated in toxic, cyanide-based chemistry. Due to cyanide’s extreme hazard to human health and environments, developing non-cyanide silver chemistry is essential for the silver electroplating industry. Discussed here is an aqueous, alkaline non-cyanide silver plating technology, which can be directly plated over nickel as well as copper and its alloys. The silver deposits have perfect white color and better anti-tarnishing properties than other non-cyanide silver processes. The silver is plated entirely from the dissolving silver anode and the bath is very stable, and maintains a stable pH level both during plating and idle time. This new non-cyanide silver technology will plate bright silver that is perfectly suitable for electronic, industrial and decorative applications. .

-

Qualitative Approach to Pulse Plating

In 1986, the AESF published Theory and Practice of Pulse Plating, edited by Jean Claude Puippe and Frank Leaman, the world’s first textbook on pulse plating. A compendium of chapters written by experts in this then-emerging field, the book quickly became the authoritative text in pulse plating. What follows here is the opening chapter, serving as an introduction to the field. Although the field has grown immensely in the intervening 35 years, the reader will find that the material remains a valuable introduction to those looking to advance the field of pulse plating.

-

Cyanide-Free Electroplating of Cu-Sn Alloys

This paper is a peer-reviewed and edited version of a presentation delivered at NASF SUR/FIN 2012 in Las Vegas, Nev., on June 13, 2012.