Metals Loading Study Supports Milwaukee Finishers' Stand Against Regulations: Then and Now

In July of this year, our NASF Report featured a major success for the surface finishing industry, the results of a 2014-2016 study of wastewater discharged to the POTWs in Milwaukee. What follows here is the story going back 30 years, when an initial study of Milwaukee metal finishers’ discharge to the POTWs dramatically refuted the negative image portrayed by others. It’s only gotten better since.

#regulation #nasf #pollutioncontrol

Metals Loading Study Supports

Milwaukee Finishers' Stand Against Regulations:

Featured Content

Then and Now

Technical Editor’s Prologue

In July of this year, our NASF Report featured a major success for the surface finishing industry in the results of the NASF metals loading study for wastewater discharges. The article gave us the results of a 2014-2016 study of wastewater discharged to the publicly owned treatment works (POTWs) in Milwaukee. Spearheaded by John Lindstedt, NASF Fellow, President of Advanced Plating Technologies (Milwaukee), and longtime advocate in representing our industry, the study showed the industry to be highly successful in meeting and exceeding the EPA 40 CFR Parts 413 and 433 Metal Finishing Effluent Guidelines.

What follows here is the story going back 30 years, when an initial study of Milwaukee metal finishers’ discharge to the POTWs dramatically refuted the negative image portrayed by others. The current study shows that our industry, rather than resting on those laurels, has continued to strive further in these efforts. But first, we offer the original paper, published in 1992, containing the 1989-1991 results and the methodology (which was actually used in both studies). Following this, a concluding epilogue summarizes the impact of both studies. A printable version of this entire offering is available by clicking HERE.

Metals Loading Study Supports

Milwaukee Finishers' Stand Against Regulations

by

John S. Lindstedt

Advanced Plating Technologies

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA

Editor’s Note: This paper was originally published as Plating & Surface Finishing, 80 (4), 30-35 (1993).

ABSTRACT

Between June 1991 and July 1992, the Milwaukee surface finishing industry was required to respond to new proposed local regulations from its publicly owned treatment works (POTW) - the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD). Area finishers felt the regulations were extreme, prohibiting 26 organic and inorganic substances at the limit of detection. Hexavalent chromium (Cr+6), for example, was limited to 1.00 ppb and mercury to 0.2 ppb. In order to challenge these regulations with sound engineering data, Milwaukee-area finishers commissioned an engineering firm to conduct a study to determine the amounts of effluents attributable to permitted industrial users. The study resulted in relaxation of the most stringent requirements.

Proposed stringent regulations by the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD) in 1991 prompted Milwaukee surface finishers to defend their operations. During the interactive regulatory process concerning the proposed regulations, the metal finishing industry was portrayed as an undesirable member of the "environmental community" by the MMSD and environmental groups. Their position was based on the assumption that the industrial contribution of pollutants to the POTW was often the major source of the pollutants. The name "metal finisher" or "electroplater" was synonymous with polluter!

Industry representatives took a proactive stance to provide factual information regarding the amount of categorical pollutants that their operations were introducing into the system. A study was commissioned by the Metal Finishing Defense Fund. It was intended to demonstrate, with three years of data (1989-1991), that industry had not abdicated its environmental responsibility, but was instead doing its share to be a responsible member of the "environmental community." The study was to determine the average daily mass loadings of categorical pollutants introduced to the influent of the MMSD system from all permitted industrial users. These pollutant loads would be compared to the total daily pollutant loads received by the POTW. The percentage of the load attributed to industrial users would then be calculated.

In addition to data collection on its own members, industry became very outspoken on "equitable environmental responsibility" (i.e., the fair sharing of responsibility for environmental damage and remediation of that damage). Although industry continues to be the greatest source of toxic discharges into sewage treatment plants, other sources are contributing increasing amounts of regulated toxic pollutants. Households contribute 15% of the pollutant load received at a typical POTW.1 The residential community is a significant source of heavy metals; elimination of industrial wastewaters would not completely remove all problems caused by heavy metals.2 The Gurnham Study, "Control of Heavy Metal Content of Municipal Wastewater Sludge," clearly demonstrates that significant concentrations of metals (0.02 pg/L of mercury, 2 pg/L of cadmium and 200 pg/L of zinc) are commonly found in residential effluents. These concentration levels, when evaluated with the large flow associated with the residential community, result in significant metal loading to a POTW. Moreover, as industrial discharges decrease, the proportion that household waste bears to the whole will increase.

The same is true for non-regulated industrial sources. Numerous organic and inorganic pollutants are generated in significant amounts from this segment of the community. The contribution to POTWs of 1,2-dichloroethane, bromo-dichloro-methane, trichlorethylene, and benzene from commercial sources exceeds 10% for each and, in the case of benzene, accounts for 50% of the pollutant load.1

The position of the Milwaukee metal finishing industry was that if the community is truly concerned about the quality and type of pollutant loads entering the environment, then it must identify and address all pollutant sources equally. The contribution from the industrial, residential and commercial (non-regulated industry) sources must be given equal weight, as each contributes a significant pollutant load to the environment. Industry concurred with General Accounting Office recommendations that would:1

- Require treatment plants (POTW) to implement source control programs (e.g., regulating additional industrial and commercial discharges and establishing programs to collect household hazardous wastes);

- Exercise the EPA's authority under the Toxic Substance Control Act to restrict or ban substances, or require manufacturers to place warning labels on their products to alert customers to a risk if those products have the potential to cause severe environmental damage.

The study

An engineering firm was retained by the Metal Finishing Defense Fund to conduct a study to determine the average daily mass loadings of certain metals being discharged by the electroplating and metal finishing industries into the MMSD. Metals and combinations within the scope of the study included cadmium, chromium, copper, nickel, lead, zinc, silver and total cyanide. The study was to determine the percentage of the MMSD influent loadings of these metals attributable to the electroplating and metal finishing industry. For purposes of this study, the metal finishing industry was defined as all industrial users within the MMSD service area subject to either the Part 413 Electroplating Pretreatment Standards or Part 433 Metal Finishing Pretreatment Standards.

The findings are presented on both worst case and best-case bases. The worst case/best case designations refer specifically to the way in which data reported at less than a specified level of detection were used with the study. In the worst case, all values reported at less than a specified level of detection were assumed to be equal to that level of detection. In the best case, all values reported as less than a specified level of detection were assumed to be equal to zero. The study also delineates the procedures and data used to calculate total influent metals loadings to the MMSD system, as well as the procedures and data used to calculate the average daily metals loadings attributable to the metal finishing industry.

Findings and conclusions

Worst case

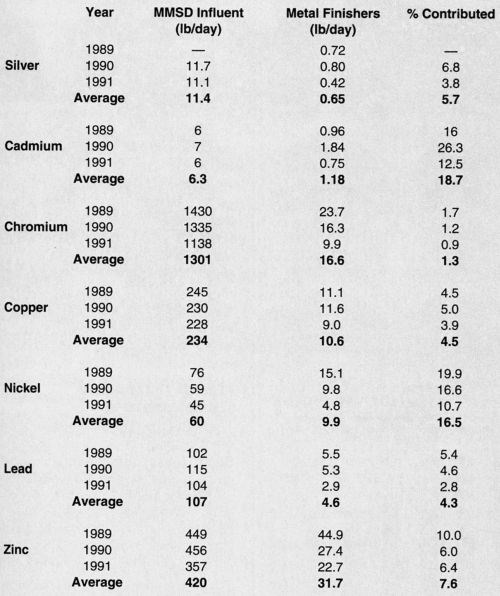

In the worst case, all industrial-user monitoring data reported at a concentration less than a specified level of detection were assumed to be present at a concentration equal to the reported level of detection. For example, a value reported as less than 0.02 mg/L was considered equal to that value. Table 1 presents a summary of the study findings for this worst case. For each metal studied, the table shows the average daily total influent loading to the MMSD system, the average daily influent loading to the MMSD system contributed by the metal finishing industry, and the percentage of the MMSD influent loading attributable to industry. As shown, on average, the metal finishing industry was responsible for 5.7% of the silver, 18.7% of the cadmium, 1.3% of the chromium, 4.5% of the copper, 16.5% of the nickel, 4.3% of the lead and 7.6% of the zinc that entered the MMSD system during the period 1989 to 1991 (three-year average). It should be noted that no MMSD influent loading data for silver was available for 1989.

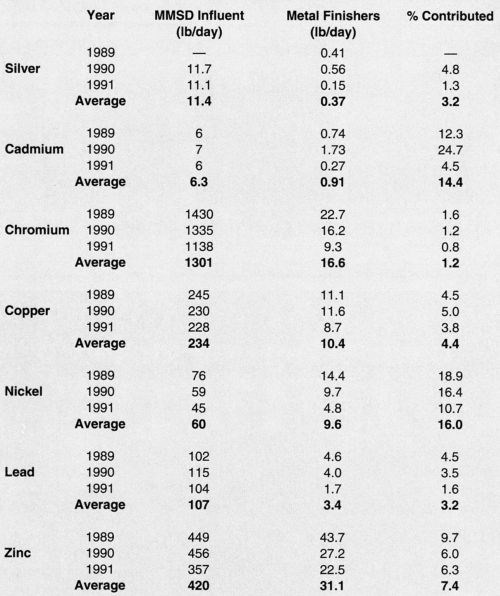

Table 1 - Summary of study results - Worst case.

Best case

In this case, all industrial-user monitoring data reported at level-of-detection concentrations were set equal to zero. For example, a value reported at less than 0.02 mg/L was converted to a value of 0.00. Table 2 presents a summary of the study findings for this best case. When compared to the worst case, significant reductions were observed in the contributions attributable to the metal finishing industry for silver (5.7 to 3.2%), cadmium (18.7 to 14.4%) and lead (4.3 to 3.2%), the metals that showed significant change.

The best case/worst case comparison offers a strong argument for the proper way to report low levels of analytes. Obviously, reporting of levels that are below the level of detection, as at the level of detection, is incorrect. This results in artificially high levels of pollutants that raise public concern and do not represent an accurate environmental picture of the pollutant load. Likewise, reporting of analyte levels that are less than the level of detection as zero is also incorrect. This would provide an over-optimistic environmental picture. What is needed is:

- To report levels that are below the level of detection as just that - less than the level of detection - or not detected;

- Better analytical procedures to quantify low-level pollutants;

- Regulatory agencies that require logical, technically based reporting schemes for analytes that are typically found at less than their level of detection.

Table 2 - Summary of study results - Best case.

Cyanide

As part of this study, an attempt was made to quantify the total cyanide loadings attributable to the metal finishing industry. Although total influent loadings of cyanide into the MMSD system could be calculated, it was virtually impossible to calculate the metal finishing industry's contributions for a number of reasons:

- Facilities subject only to the Part 413 Electroplating regulations, and with process wastewater flows less than 10,000 gal./day, are regulated only for amenable cyanide.

- Because the appropriate type of sample for cyanide analysis is a grab sample, in most cases no flow data was provided; therefore, mass calculations could not be performed.

- For facilities subject to the Part 433 Metal Finishing regulations, monitoring for cyanide must be conducted after cyanide treatment, prior to dilution with other wastestreams. Most flow data reported represented the total treatment plant flow and therefore was inappropriate for use in mass-based calculations.

MMSD database development

The MMSD comprises two sewage treatment plants, Jones Island and South Shore. These plants are capable of being cross-connected and are typically operated in that mode. The data for the years 1980 to 1990 were obtained from the MMSD's 1990 Industrial Wastewater Pre-treatment Program Effectiveness Analysis, Chapter 2, "Summary of Treatment Plant Operations." The preparation of this report is a requirement of the MMSD's WPDES discharge permits, and requires the MMSD to quantify the influent and effluent loadings of various metals into its system.

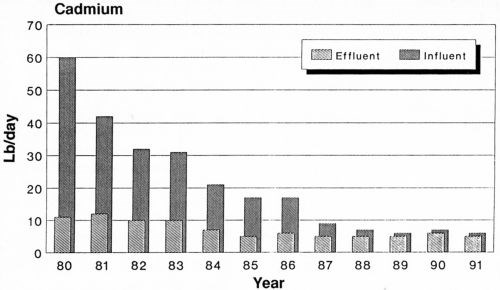

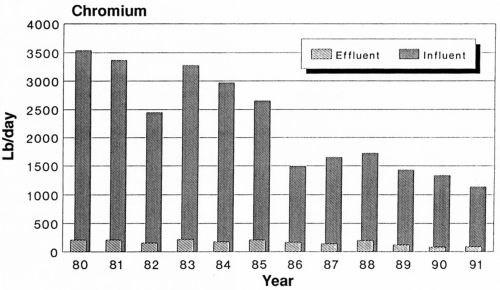

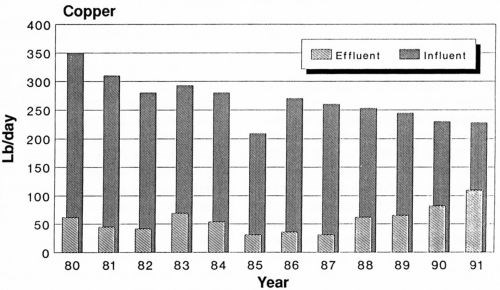

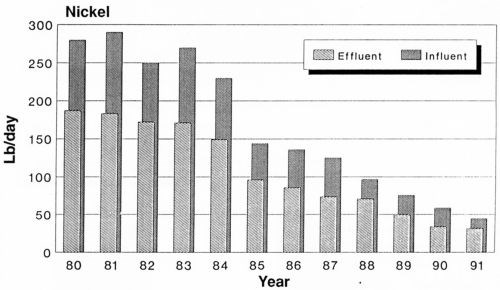

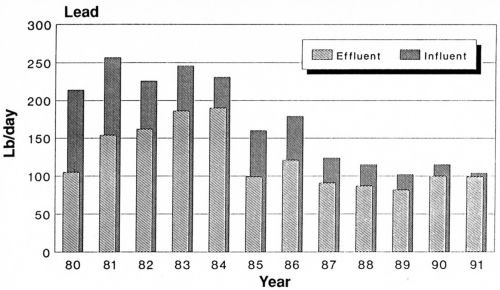

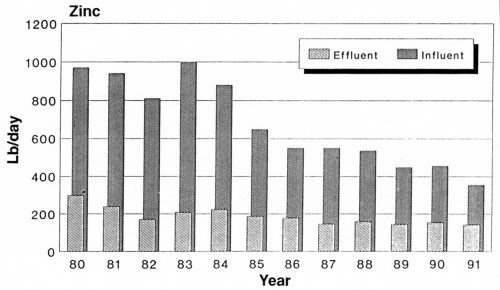

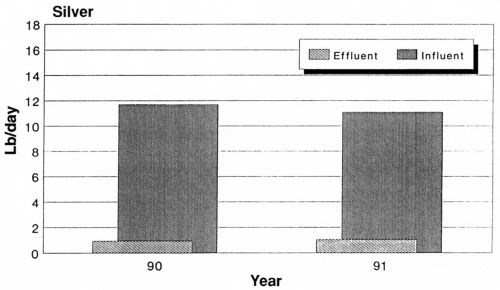

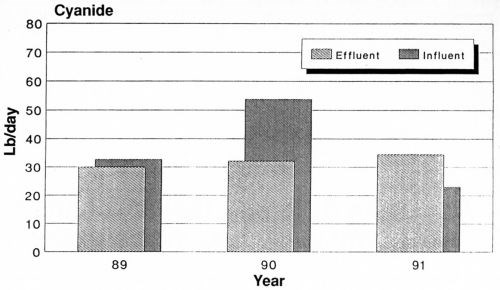

Figures 1 through 8 provide a graphic presentation of the influent and effluent metals loading data for both the Jones Island and South Shore Treatment Plants for the period 1980 to 1991. Except for silver and total cyanide, these figures clearly show the significant reductions in influent metals loadings observed by the MMSD since the implementation of its industrial waste pretreatment program in 1984. With respect to silver, historical data prior to 1990 is limited and was not available for purposes of this study. Regarding total cyanide, Fig. 8 is interesting in that for 1991 it shows that the MMSD reported more cyanide to be present in its effluent than was observed in its influent. The data from both plants were combined in order to determine the total system loadings. This was necessary because it is extremely difficult to determine which treatment plant a number of the electroplaters and metal finishers discharge to, because of diversion areas within the MMSD system.

Figure 1 - Total influent and effluent cadmium, 1980-1991

Figure 2 - Total influent and effluent chromium, 1980-1991.

Figure 3 - Total influent and effluent copper, 1980-1991.

Figure 4 - Total influent and effluent nickel, 1980-1991.

Figure 5 - Total influent and effluent nickel, 1980-1991.

Figure 6 - Total influent and effluent zinc, 1980-1991.

Figure 7 - Total influent and effluent silver, 1990-1991.

Figure 8 - Total influent and effluent cyanide, 1989-1991.

Industrial-user database development

To determine the influent metals loadings attributable to the electroplating and metal finishing industry, the engineering firm utilized the MMSD's industrial-user compliance database. This database includes the results of all self-monitoring conducted by the MMSD. Using the MMSD's 1990 Industrial Wastewater Pre-treatment Program Effectiveness Analysis, the engineering firm assembled a listing of each industrial user subject to either the Part 413 Electroplating or the Part 433 Metal Finishing categorical pre-treatment standards. Approximately 85 industrial users were identified through this process. A records request was then submitted to the district for all of the monitoring data in its industrial-user compliance database for each regulated electroplater or metal finisher. These data were requested for the years 1989,1990 and 1991.

A BASIC computer program was developed to extract all of the valid monitoring data. Only data points with an associated flow value were extracted because mass loadings needed to be calculated. Sample results for which no flow value was available were not used in the study. Data extracted included the company name, its MMSD permit number, the outfall from which the sample was collected, the page of the MMSD hard-copy printout where the data point can be found, whether the sample was analyzed by the MMSD or by the industrial user, the date of the sample, the sample type, the volume of flow, and the sample results for the various metals expressed in mg/L. These data were then used to calculate average pounds per day loadings for each metal for each individual user. Where users had multiple outfalls, average loadings were calculated for each individual outfall.

Prior to calculating the average pounds per day loadings, the database was screened to eliminate all data points clearly associated with either a spill or upset condition (identified by extremely high effluent concentrations). Because the intent of the study was to represent average operating conditions, these points were deemed to be not representative of normal operations and, if left in the database, would produce misleading results. The final step in the process was to sum the individual loadings to produce a total industry loading for each year.

Compliance evaluation

The Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District is required by the EPA to conduct periodic evaluations of its industrial users to identify those in significant noncompliance (SNC). The MMSD defines SNC as:

(a) Chronic violations

Sixty-six percent or more of all measurements taken during a six-month period exceed by any magnitude the daily maximum limit or the average limit for any one pollutant;

(b) Technical review criteria violations

Thirty-three percent or more of all measurements taken during a six-month period for a particular pollutant equal or exceed the product of the daily maximum limit or the average limit for that pollutant multiplied by:

- 4, for BOD, TSS, fats, oil and grease;

- 1.2, for all other pollutants except pH; or

- 1 for pH.

The six-month periods referred to in this definition run from January 1 to June 30 and from July 1 to December 31. During the three-year time period covered by the study, there were six such evaluation periods.

A review of the SNC evaluations for these six time periods shows a substantial reduction occurred in the number of metal finishers found to be in SNC from January 1989 to December 1991. From January to June 1989, 49% of the metal finishers had at least one occurrence of SNC (40 out of 75).

Another way to look at compliance is to compare the total number of opportunities for metal finishers to be found in SNC to the actual number of times SNC occurred. From January to June 1989, there were 3,416 separate opportunities for metal finishers to be found in SNC and only 161 actual instances. This is a percentage of SNC of 4.7. From July to December 1991, there were 2,958 separate opportunities for SNC to occur and only 30 actual instances - one percent. In summary, there was a significant improvement in the compliance status of the metal finishing industry during the three-year study.

Following presentation of the study to the MMSD, adverse comments about the metal finishing industry ceased. There was recognition that there had been faulty perception of the role played by platers and finishers in contributions of pollutants to the POTW. The requirement for hexavalent chromium was deleted and the organics were simply prohibited, but the burden of proof of violation now rests with the MMSD. The study has generated considerable interest in other communities (e.g., St. Louis, MO), where efforts are being made to perform similar studies.

Bibliography

1. Report to the Chairman, Committee on Environment and Public Works, U.S. Senate, "Water Pollution; Non-industrial Wastewater Pollution Can Be Better Managed," U.S. General Accounting Office: B-245695, Washington, DC (Dec. 5,1991).

2. Technical Report, C.F. Gurnham, et al., "Control of Heavy Metal Content of Municipal Waste Water Sludge," NSF Grant No. ENV77-04355, Washington, DC (April 1979).

About the author [1993]

.jpg;maxWidth=600)

Technical Editor’s Epilogue

Over a quarter century had passed when the EPA decided to look into revising those metal finishing guidelines for wastewater discharges. Such developments were not out of the ordinary. Like trade agreements and international treaties, the passage of time often gives rise to issues that were not present initially and need to be addressed. The EPA was “doing its job.” In response, Mr. Lindstedt repeated the work that had been done 27 years earlier.

For the sake of brevity, the new results corresponding to the material provided in the earlier paper are not presented here. Nonetheless, the outcome of the second study was exceptionally positive.

Total lead discharged to POTW averages 32.57 lb./day in Milwaukee, of which 0.07 lb./day is attributable to the metal finishing industry. For nickel, 1.33 lb./day of the total 15.43 lb./day is borne by metal finishing. For zinc, the figures are 3.59 of 220 lb./day. Taken as a whole, from 1992 to 2016, individual users experienced an average reduction of 72% for all metals (including chromium, copper, lead, nickel and zinc) between the first and most recent studies. Metal finishing is only a minor contributor. Quoting Mr. Lindstedt at the 2017 Washington Forum, “This is great news!”

Of course, the number of shops in Milwaukee had declined over the years for many reasons. Not least was the state of the economy over those years. Virtually half of the 104 shops existing in 1993 survived to 2016. And yet the decline was only partly related to the 72% reduction in discharge. Indeed, fewer shops were producing more metal than before, with less wastewater discharge. Many shops had learned to survive in the adverse economic times of the first decade of the 21st century. These survivors used more efficient state-of-the-art operational control technologies and pollution prevention techniques. Thus, metal finishing pollution was nearly a thing of the past.

Milwaukee, of course, is just one data point in the industry picture. In discussions within the industry, this picture represents the state of the nation as a whole. From a technological standpoint, wastewater management methods are uniform across the board. And nationally, fewer shops exist, but produce more metal with significant reductions in wastewater discharge.

The NASF presented the new data to the EPA with the message that revision of the existing guidelines was not necessary. It remains for the agency to make such a revision at this time. But thanks to the efforts of the NASF and the leadership of Mr. Lindstedt in this work, the outlook is bright and has gotten better over these years. And the surface finishing industry can be proud of the great strides made.

About the author [2017]:

.jpg;maxWidth=600)

RELATED CONTENT

-

Evaluation of Atmospheric Corrosion on Electroplated Zinc and Zinc-Nickel Coatings by Electrical Resistance (ER) Monitoring

This paper is a peer-reviewed and edited version of a presentation delivered at NASF Sur/Fin 2013 in Rosemont, Ill., on June 12, 2013.

-

Plastics and Plating on Plastics [1944]

This republished 1944 AES convention paper presents an historic perspective of the early days of plastics in surface finishing - using them and plating on them, in the waning years of World War II. The discussion reviews the uses of plastics in plating equipment and processing at that time, as well as the coating of the plastics themselves, with accompanying application photos. You will note that today’s conventional plating-on-plastics processes lay far in the future. Surprisingly, CVD processes are discussed.

-

Cyanide-Free Electroplating of Cu-Sn Alloys

This paper is a peer-reviewed and edited version of a presentation delivered at NASF SUR/FIN 2012 in Las Vegas, Nev., on June 13, 2012.