Rebuilding the KEI Plating Giant

Oscar Kuntz’s grandsons have turned around the automotive plating firm from the brink to success again.

#masking #automotive #pollutioncontrol

Before the name Kuntz became known all over Canada as the biggest and one of the best electroplating companies in the industry, it was famous for a few other things.

Back in the 1840s in Waterloo, Ontario, David Kuntz went from making beer in a wooden washtub and selling it from his wheelbarrow to buying his own factory and starting Kuntz Brewery, becoming Canada’s second-best selling beer by World War I.

Featured Content

Kuntz eventually merged with Carling Breweries, which finally became known as Labatts today, but many people still recall Kuntz Brewery as the “the beer that made Waterloo famous.”

In the 1950s, Bobby Kuntz put on a football helmet and played for the Canadian Football League’s Toronto Argonuats and then the Hamilton Tiger-Cats, becoming one of the best CFL running backs in league history, winning two championships along the way.

Then came Oscar Kuntz, a descendent of David, and also Bobby’s father. He started Kuntz Electroplating in 1948 after receiving his degree in chemistry from Fordham University in Detroit. The company that began in Waterloo, Ontario, nearly 70 years ago is much different than the one now located in Kitchener, about 90 minutes west of Toronto.

The current KEI leaders are Mike Kuntz, John Hohmeier, Robert Kuntz Jr., Dave Kuntz and Jeff Regehr

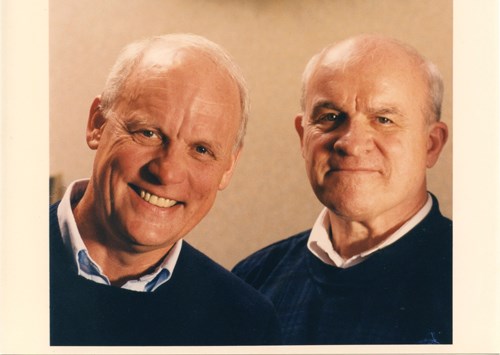

The late Bob and Paul Kuntz were the sons of founder Oscar Kuntz.

Bob Kuntz inspects bumpers produced by the company.

Walk into the 400,000-square-foot facility that runs three shifts, five days a week, and you will find more than 450 employees plating and polishing metal like no other facility in North America.

Big Names in Automotive

Take a closer look at the chromed wheels and parts, and the names Harley-Davidson, General Motors, Toyota, Honda, BMW, Jaguar, Mercedes, Volvo, Nissan, Rolls-Royce, Bentley and Freightliner pop up, among others.

A Tier 1 and Tier 2 supplier, Kuntz Electroplating Inc. (KEI) offers nickel-chrome electroplating primarily on steel and aluminum but also on zinc and other substrates. It has full in-house polishing, metal finishing and buffing services; high-quality die casting, stamping, forging and extrusion capabilities through its world-class partners; offers subassembly, engineering and design support; and has both destructive and non-destructive testing facilities.

Today, third-generation Kuntz family members are now heading up the company—all grandsons of Oscar Kuntz. Mike Kuntz is vice president of sales and marketing of KEI, Robert is vice president of process improvement and Dave is vice president of operations.

While Canadians know the Kuntz name from the beer and the football star, it is the electroplating company that has become a major force in the country’s manufacturing sector. More than 70 percent of the parts it processes are automotive, with the balance being motorcycle and recreational vehicle components.

“We live and die by the automotive industry,” Mike Kuntz says. “It is very much cyclical, but we have weathered the storms that come up because we are versatile and flexible. In some ways, it has made us stronger.”

More than 70 percent of KEI's process are automotive; the remaining percent is composed of motorcycle and recreational vehicle components.

For many decades, the company offered dozens of finishes to the many different markets. But then came the realization in the early 1980s that there were very few electroplaters producing high-volume decorative nickel chrome on metal substrates such as steel and aluminum. That’s when KEI shut down some finishing lines and made its focus nickel chrome … lots and lots of nickel chrome.

Niche Plating

“We carved out our own niche,” Mike says. “It was a risk, but we knew what we could do, and we knew we could do it very well. That became our focus, and we don’t regret it one bit.”

Oscar Kuntz brought his sons in to help run the business during the surge in the 1950s and ’60s. Dave, Paul, Louie and football star Bob all helped KEI grow into one of the biggest electroplaters in the world. When Dave passed away in 1961, Bob took over as managing director of the company.

KEI grew exponentially in the coming decades. In 1965, the company left its Nyberg Street location for a new industrial park on Wilson Avenue, but over the years even that facility was too small. KEI built on 6,000 square feet, then leased another 5,000 to add more polishing stations, bringing employment to more than 100.

In 1973, the company had doubled its square footage to 52,000 when it added facilities for maintenance, lab, quality control, shipping and new automotive lines. By 1978, KEI had added more space in its main plant for an aluminum line, but it also made the major decision to become a division of Magna Industries to help broaden its automotive services on a global level.

Rebuilding the KEI Plating giant.

Magna owned 60 percent of KEI, and Bob was the general manager with Paul serving as assistant GM. Quickly, the company grew to more than 450 employees with more than 125 customers in Canada, Michigan and the midwestern portion of the U.S.

“What really made it for the company was when we joined Magna,” Paul said in the company’s newsletter in 2002. “That really got us into the big leagues. When Magna bought us, we immediately put in the hoist aluminum line and started plating on aluminum. There was virtually nobody plating on aluminum at the time or in large scale. We became the gurus of plating on aluminum.”

750,000 Square Feet

Magna’s ownership lasted until the early 1990s when KEI went private again. By then, it had cemented itself as one of the top electroplaters and metal finishers in the world, mastering copper/nickel chrome plating on both steel and aluminum bumpers, and providing zinc, phosphate and other specialty finishes, too.

As a now-private entity, KEI added more than 450 employees toward the end of the 1990s to bring its total to more than 1,000 employees by the new millennium, with more than 750,000 square feet of plating and polishing space.

Workers still do some buffing and polishing by hand, especially on the running boards.

By the mid-2000s, KEI signed Harley-Davidson and Leggett & Platt as customers, and built new plating lines designed specifically to meet Harley-Davidson’s requirements for cosmetic nickel chrome finishing for die cast aluminum applications. It took two years to design and build, but the line used hi-tech, computer-controlled, automated hoist systems and other cutting-edge control technologies. With the addition of advanced robotic polishing equipment, the new line has an annual output of more than three million parts for Harley-Davidson.

About the only thing that could stop KEI’s phenomenal growth was a perfect storm, and that occurred with the recession of 2008 that resulted in the bankruptcies of General Motors and Chrysler. It was a significant challenge to KEI, one that forced them to look at all aspects of its electroplating and polishing operations to see where it could refine performance, eliminate waste and prepare itself for the future.

That meant KEI began embracing a new lean manufacturing culture, one that started at the top of the company in its management team and worked its way to every employee. Buy-in was essential, and it turned out that KEI employees were ready to embrace the new culture in order to keep the company competitive on a global scale.

“Without our employees’ dedication and determination in finding the least-waste-way in everything we do, we would not be here today,” Mike says.

In fact, the KEI management team saw the need for change even before the huge recession of 2008 began hitting companies all over the world. Mike Kuntz says that the appreciation of the Canadian dollar became apparent early in the 2000s, and the 2006 closing of the BF Goodrich plant across the street was a sure sign of impending economic trouble for the manufacturing sector.

Surviving

All of which meant that the changes the KEI owners made earlier in the 1990s to become a specialized electroplating operation instead of offering dozens of different finishes paid off when a lot of finishing work went overseas to China, or south to Mexico.

“The shops that are left are the ones that are specialized,” Mike Kuntz says.

But it was still a major financial hit when some of the Big Three automakers underwent a dramatic change as recession hit and manufacturing began to suffer tremendously. That’s when the KEI management team—spearheaded by John Hohmeier, a seasoned, veteran president hired from the outside, along with Mike, Robert and Dave—committed the company to even more dramatic changes.

KEI was operating with more than 650 employees when the worst of the financial crisis reared its head. Not only were some of its biggest automotive customers in trouble, but KEI and others were also being pinched in raw material costs as nickel skyrocketed almost 400 percent.

KEI’s wheel business was in decline, and although new business was coming in, it was not growing fast enough to offset losses. At the same time, its key lender decided it wanted out.

“The timing couldn’t have been worse,” says Mike. The lender suggested KEI find help and allowed the company time to restructure the business. It was at that time that the Kuntz families sought the expertise of the Keystone Group, and Mike, David, Robert Kuntz and the rest of the management team rolled up their sleeves and began the arduous task of saving their company.

Each robotic cell can work on 10 wheels situated on a large turntable to keep production flowing.

“We were in a fair bit of trouble,” says Robert Kuntz. “We had consultants in before, but without any lasting results.”

The employees responded well, accepting concessions to reduce costs and embracing the company’s Lean Transformation—the arduous but necessary journey to right-size the business, eliminate waste and ensure a globally competitive company.

Improved Operations

KEI managers focused on the day-to-day operations and found several areas for improvement. They instituted productivity measures that reduced reject rates from 15 to 6 percent, and they increased the company’s polishing and buffing efficiencies to net the company more than $3 million in annual cost savings.

Additional steps included reducing production material costs to save $1.7 million, and passing on the increased cost of nickel to customers, a practice KEI had never really done when material costs were so incremental.

KEI also reduced its fixed costs on items such as plant services, saving another $2 million annually, and more importantly, the management team became more aggressive in bidding on new business outside of automotive to help stop the fall in total sales.

KEI’s leadership initiatives helped the company rebound swiftly from nearly going over the ledge. The company broke even three months ahead of its planned schedule, making ends meet in just four months and paring down its overall debt by more than $6.5 million.

“The consultants were the first ones we had that really made a difference,” Robert says. “They helped us chop $11 million in annual costs from our bottom line, and literally that helped save our skin.”

Where KEI once had more than 1,000 employees working in its shops in Kitchener, it now employs fewer than 600, thanks in large part to line automation and to a major investment in robotic polishing units that mimic the delicate human touch with amazing accuracy and precision. These robotic systems are controlled and maintained by highly skilled workers and an automation team that includes programmers, electricians and robotic experts.

With many of the parts trending toward deep contours, KEI's management decided to investigate fixed robotic cells.

Robotics

Most of the robotic work is centered in running boards and the motorcycle part areas. With parts trending toward becoming more deeply contoured, KEI’s management decided to investigate fixed robotic cells to handle the hundreds of thousands of parts that needed grinding and polishing before being chromed.

“You need the absolute best, most polished surface in order to get the best chrome finish,” Mike says. “Chrome will accentuate any blemish on the metal substrate, so it has to be polished to near perfection or it will be noticed by the customer.”

KEI spent a considerable amount of time researching the robotics machines on the market before deciding that it would need to help design the cell units to specifically meet it needs. One of the realizations was that a fixed polishing setup would not work because of the contours of the part; the polishing robot would need to move all around the part in order to get into the smallest areas.

Wheel specifications called for a variable-speed, high torque machine that was capable of automatic media change—the polishing and buffing wore down pads at a very high rate, and several different grits would be needed. In the 1990s, KEI began working with Fanuc Robotics in Rochester Hills, Michigan, to build the robotic processing equipment, and they also engaged PushCorp in Dallas to help build a critical piece of the system, the end-of-arm tooling that moved the polishing wheels around the part in a synchronized fashion.

Early on, KEI made a major investment of 20 robots from Fanuc, installing two robots each into 10 cells on the shop floor. Each cell could work on 10 wheels situated on a large turntable to keep production flowing.

Today, the company uses more than 25 automated and semi-automated robotic polishing systems.

“We’ve embraced technology and innovation as a way to remain globally competitive and believe in keeping supply chains short,” Mike says.

Originally published in the July 2015 issue.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Troubleshooting for Electrocoating

Characterizing the type of defect is essential in identifying the root cause and eliminating its source...

-

Painting a Boeing 737: See The Video

The cost is between $100,000 to $200,000 to prep and paint each plane, depending on which colors are chosen, and how many colors.

-

Applications Innovation Leads to Better Masking Solutions

When masking product failures are costing you money, it pays to work with an expert that can select or engineer the most efficient solution.