The $178 Billion Plating Shop

Go inside the Plate Manufacturing Division of the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing’s picturesque building at 14th Street SW in Washington, D.C. The BEP is this nation’s sole producer of U.S. paper currency, also known as Federal Reserve Notes.

Chances are, if you’ve bought a drink at a ball game, given your kids $5 to buy an ice cream or plunked down money for a movie ticket, you have touched the handiwork of Steven Olszowy and his team at the Plate Manufacturing Division of the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP).

Olszowy is the supervisor of the division, which is housed inside the BEP’s picturesque building at 14th Street SW in Washington, D.C. The BEP is this nation’s sole producer of U.S. paper currency, also known as Federal Reserve Notes. Olszowy’s division makes this production possible.

Featured Content

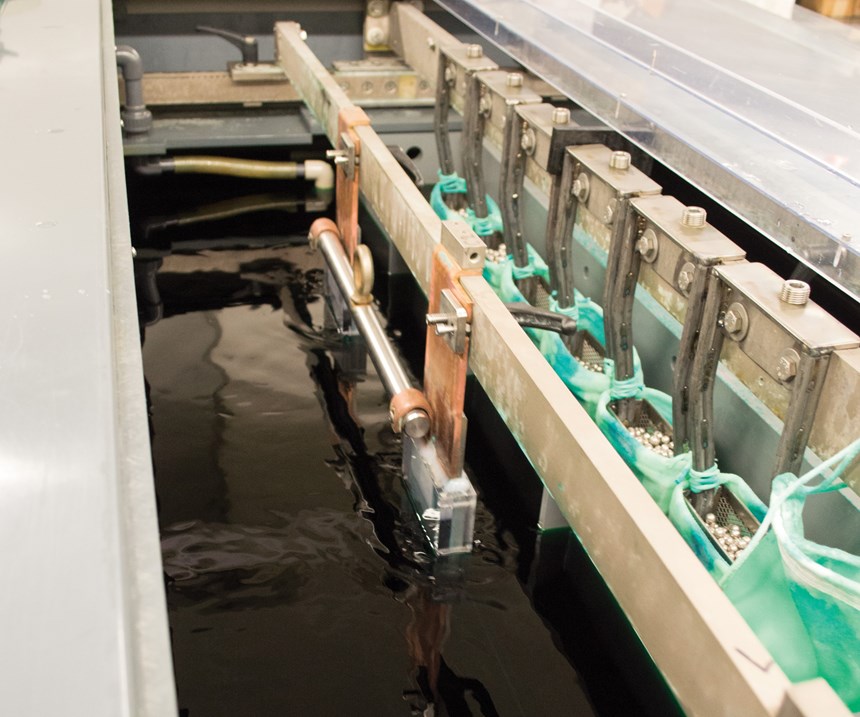

“It’s a printing process, but it all starts with the printing plates,” he says. His shop makes use of six nickel baths and three chrome baths to make roughly 500 printing plates each year.

“We electroform a base nickel plate, then we chrome that nickel plate to get the wear and the life we need to last as long as it can on the presses,” he says.

It takes the 700-gallon nickel baths about 17 hours to give the printing plates the necessary 1,000-micron finish. Another 45 minutes in the chrome baths adds an 8-micron protective layer.

“We do the same as any other plating shop in the U.S.,” Olszowy says. “It’s just that what we are working on has a little more higher visibility than maybe other parts out there being plated.”

More Than Just Money

But money isn’t the only item the BEP designs and produces for the federal government. Scott Green, chief of the Office of Engraving, says the agency also creates and prints a variety of other products at its production facilities in Washington and Fort Worth, Texas, including military commissions and award certificates; invitations and admission cards; as well as many different types of identification cards, forms and other special security documents for a variety of government agencies.

“We also make plates for passports, birth certificates and souvenir cards—whatever they need from us,” Green says. “Currency is our primary mission, but we have a large miscellaneous program to print for the State Department, the Government Printing Office and others.”

The BEP does not produce coins, which are made by the U.S. Mint, but it churns out metal plates used to produce $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50 and $100 notes to the tune of about

7 billion notes a year worth about $178 billion.

Olszowy’s operation includes a staff of 12 journeymen platemakers and three apprentices whose job it is to create workable printing plates that can withstand 28 tons of pressure from the printing presses.

“Our goal is to get about 1 million impressions from each plate,” Olszowy says. “But that is a lot of pressure, so the chrome wear needs to be sufficient to get us to that point.”

Green Operation

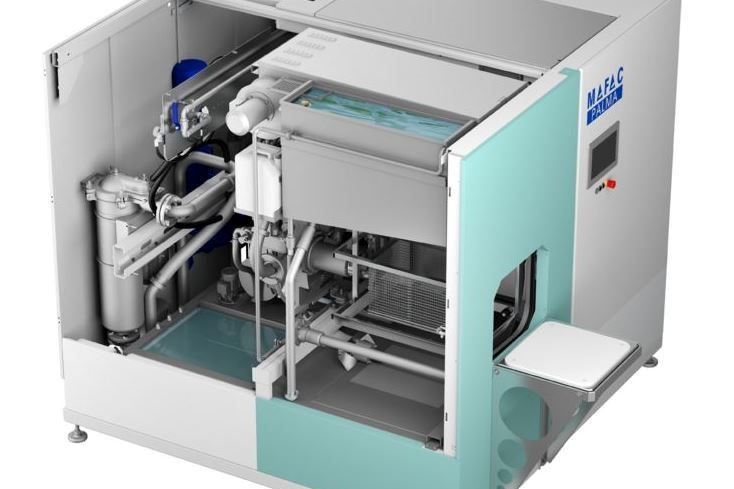

Just like any other plating operation in the U.S., the BEP plating division has to meet environmental and regulatory requirements, including District of Columbia air quality rules. The facility has installed scrubbers for its nickel and chrome lines, and recently added covers for its nickel tanks and spray shields for its chrome tanks, as well as mist-suppression balls to the line, which was installed in 2009.

“Our new system is designed to be more green environmentally with make-up air for all tanks,” Olszowy says. A second containment moat was added, as well as an on-board filtration system.

“We still face the challenge of a balancing act between system and manufacturability,” he says.

The BEP traces its roots to 1861 in legislation enacted to help fund the Civil War. That year, Congress authorized the secretary of the treasury to create paper currency instead of coins to address the lack of funds needed to support the war.

According to BEP history, the paper notes were basically government IOUs and were labeled Demand Notes because they were payable “on demand” in coin at various U.S. Treasury facilities. Because the federal government had no production facility to make paper money, however, it hired a private company to produce the Demand Notes, which were then shipped to the Treasury Department, where dozens of clerks could sign them and workers could cut and trim sheets of them by hand.

Congress created the Office of Comptroller of the Currency and the National Currency Bureau in 1863 to print newly created National Bank Notes. In the ensuing years, the currency operations were known by several titles—Printing Bureau, Small Note Bureau, Currency Department and even the Small Note Room—until 1874, when the Bureau of Engraving and Printing was given official recognition and operating funds. By 1877, Congress ordered that the engraving and printing of notes, bonds, and other securities be performed only at the Treasury Department, thus making BEP’s Plate Manufacturing Division the only one enacted by Congress.

In 1906, the BEP outgrew its facility at 14th and B streets in Washington, and a newer building was built between 14th and 15th streets to the south of the original building. That building is known as the BEP’s main building.

Texas Location

Washington isn’t the only place that currency is printed, however. In 1985, the BEP began looking for a site for an operating facility west of the Mississippi River that would help with increased currency production needs. It would also serve as a contingency operation in case of emergencies at the Washington facility. The following year, Fort Worth, Texas, was chosen as the site for the BEP’s Western Currency Facility. That facility opened in 1991.

The printing of currency and other items starts with the artistry of BEP’s designers, who create a model of the final printed product by putting together images, text and other graphic elements. When the products need engraved elements, including portraits, vignettes, ornaments or lettering, BEP engravers use the designer’s model to cut extremely fine dots, dashes and curved lines of varying depths and widths into a piece of soft steel, which becomes a master die. From there, the engraver produces a three-dimensional image on a two-dimensional surface using complex engraved lines.

Following approval of the artwork or engraved master dies, most of the work then heads to the plating division, where the originals images are transferred to the master printing plates and then to working plates that might eventually go on the printing presses (the BEP uses intaglio, gravure and offset techniques).

The Plate Manufacturing Division starts its process by getting a plastic substrate from engraving and applying a silver spray to make the first nickel substrate.

“Everything starts with a single-subject image,” Greens says.

Chrome Replacement

The division chrome-plates about 80 percent of the 500 printing plates it makes each year, Olszowy says. It is a hexavalent chrome bath, but Green says the division is working to come up with a suitable replacement within the next year. The plating lines can perform some electroless nickel operations as well, but Olszowy says that isn’t often called for.

The entire plating operation encompasses around 40,000 square feet, comparable to a typical medium- to average-size shop. The value of the goods it churns out puts it near the top, however.

“What we make turns into about $178 billion a year,” he says. “That’s still a lot.”

RELATED CONTENT

-

Smut and Desmutting

Question: I am new to this industry and have heard about smut and desmutting operations.

-

Blackening of Ferrous Metals

The reasons for installing an in-house cold blackening system are many and varied.

-

Cleaning, Pretreatment to Meet Medical Specs ISO 13485 or FDA 21 CFR820

Maximilian Kessler from SurTec explains new practices for industrial parts cleaning, metal pretreatment and decorative electroplating in the medical device industry.