Zinc Electroplating

Choosing the best process for your operation.

#basics

Zinc and its alloys have been used for more than 100 years as protective and decorative coatings over a variety of metal substrates, primarily steel. Over the years, there have been a number of processes developed for applying zinc coatings. The choice of which depends on the substrate, coating requirements, and cost. Of these, electroplating is the most prevalent for functional and decorative applications.

When choosing a zinc plating process, it is important to know what processes are available and each of their particular advantages and disadvantages. Below is a list of important factors related to these processes.

Featured Content

Factors to Consider

Listed below, in order of importance, are the primary factors to be considered when choosing a zinc-plating process:

- Does the plating specification for the part require a zinc or zinc-alloy deposit?

- Does the specification state specifically alkaline or chloride?

- Substrate(s) to be plated?

- Required corrosion protection?

- Required deposit thickness uniformity?

Considering these questions should reduce the number of usable plating processes. The next step is to consider the secondary factors. These factors listed below and will vary from shop to shop:

- Deposit characteristics (appearance, ductility, adhesion, etc.)

- Make-up and operating costs

- Operating factors (efficiency, pre-plate requirements, corrosivity, etc.)

- Environmental restrictions (air quality, heavy-metal removal, ammonia, etc.)

After fully evaluating how these factors affect your circumstances, the choice of the most applicable process should be considerably narrowed down. Here is specific information breaking down each of the different zinc-plating processes.

Alkaline Cyanide Zinc Plating

For a long time, cyanide zinc plating was the workhorse of the industry, though its popularity has significantly decreased over the years as regulations on the use of cyanide continue to grow. In its place, the use of Alkaline Non-Cyanide Zinc has taken over.

Alkaline Non-Cyanide Zinc Plating

Most available processes have eliminated the problems seen with earlier alkaline technologies with the use of an entirely new family of organic reaction products. Platers have a choice of low-chemistry alkaline non-cyanide zinc (low-metal bath) or high-chemistry alkaline non-cyanide (high-metal bath). In addition, potassium-based baths offering faster plating speeds and higher efficiencies have been introduced but come with their own disadvantage as well. The main advantage of the latest development is the ability to plate uniform thickness across the current density range. This, combined with the enhanced antiburn properties of these processes, enables increased part density on plating racks, thus resulting in high productivity.

Operating requirements for alkaline non-cyanide zinc-plating processes are as follows:

- Perform bath analysis testing on Zn and Caustic (NaOH or KOH), Hull cell testing daily. Consistent zinc levels are critical.

- Analyze, maintain and dump cleaners and acids on a regular basis.

- Perform preventive maintenance to reduce production problems and minimize costs.

- Install automatic feeders for liquid components to eliminate human error.

- For troubleshooting, follow the supplier’s recommendations carefully.

Bath makeup. Three options are available for bath makeup: using caustic and zinc oxide; using ready-made zinc concentrate; and using zinc anodes and caustic. Option A is labor-intensive. Material costs are moderate. Caution must be exercised because the reaction is highly exothermic; however, these high temperatures cannot be avoided because they are required to dissolve the zinc oxide. Option B has higher material costs, but is the least labor-intensive and the fastest. Option C is the least expensive overall, but requires a delay for zinc dissolution, as well as possible low-current-density electrolysis to remove unwanted metallic impurities. Increased use of purifiers may also be required.

Process steps. Cleaning and pickling as described above for alkaline cyanide zinc processes activates and prepares steel parts for plating. After plating, hexavalent and trivalent chromate conversion coatings can provide up to 500 hours to white salt formation per ASTM B 117. Usage of trivalent passivates now far exceeds hexavalent products, although the hexavalent products are still available. Again, strong regulatory pressure exists against carcinogenic hexavalent chrome, pushing many companies to specify trivalent finishes. A wide variety of trivalent passivates can provide colors including clear, iridescent/multicolor, yellow, and black, along with various dyed finishes. These passivates are normally used by themselves or with topcoats to provide from 12 to 700 hours of protection to white salt corrosion. Topcoats extend protection, provide additional durability, or provide a specific coefficient of friction. High end passivates combined with the newest sealer technologies can provide white corrosion numbers competitive with some alloy finishes.

Equipment. The plating tank can be made of either low-alloy steel, polypropylene, PVC or rubber-lined steel. Low-alloy steel tanks are preferred but should be insulated from the electrical circuit. For barrel operations, power of 6–15 V and a current density of 5–10 asf is recommended; for rack operations, 3–9 V and 10–40 asf. Most baths operate at a broad range of temperatures, but cooling equipment is essential and heating equipment may be needed in colder climates. Steel is the material of choice for any equipment in contact with the plating solution.

- Filters are essential for an alkaline non-cyanide zinc process. One to two turnovers of the plating solution per hour are practical in most installations using polypropylene disks or cartridges that are 5–15 microns. Paper or cellulose-type filters can be attacked by the alkalinity of the system and should be avoided. Use of a filtration system that can be carbon-packed is recommended. Mechanical agitation is optional for alkaline zinc rack operations. Air agitation should not be used due to the formation of carbonates.

- Anodes are ideally made of low-alloy steel, perforated and have a thickness of 0.125–0.375 inch. Thicker steel has a higher current-carrying capacity than thinner steel. Titanium baskets are not recommended, due to their high resistivity. Make sure low-alloy steel baskets are filled appropriately per supplier’s suggestion when zinc anodes are used. Knife-edge anode hooks make better contact than other designs. Polypropylene material is recommended for anode bags. Cotton bags will be attacked by high alkalinity and dissolve in the plating bath.

- Ensure the tops of the bags remain above the plating solution to avoid roughness. Anode-to-cathode ratio should be about 1:1; zinc metal consumption is 2.7 lb./1,000 A/hr at 100-percent plating efficiency. Plating baths can operate at anywhere from 30–80 percent cathode efficiency. This can vary depending on the zinc concentration, temperature, additive concentration and carbonate levels.

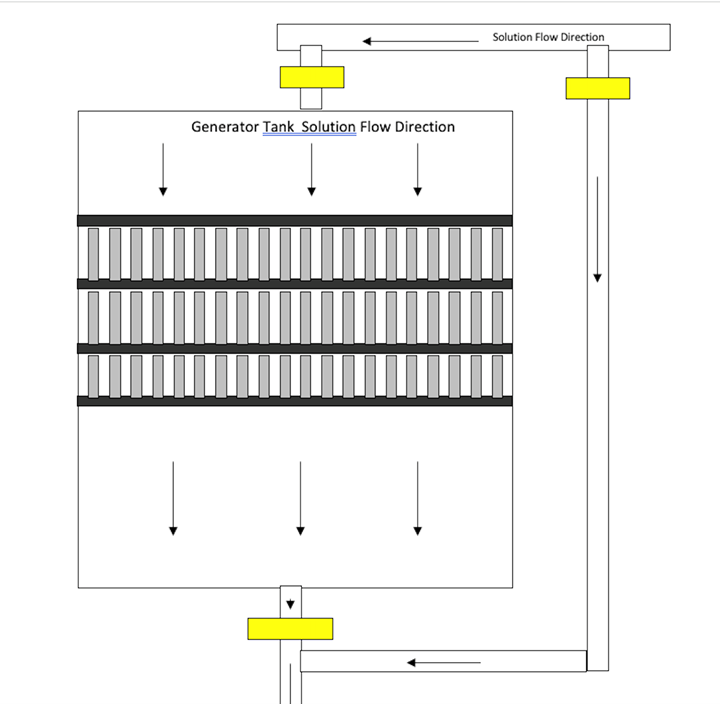

- An off-line zinc generation tank that is 10–20 percent of the volume of the plating tank makes control of the zinc concentration easy. The square footage of steel, including the tank, must be two to three times that of the zinc. The zinc anodes are galvanically dissolved in the steel tank (low-alloy steel anodes are recommended in the plating tank). Solution flow must be parallel to the baskets. The plating solution should gravity flow from the plating tank to the generator tank. The filter will receive the outflow from the generator tank and return solution to the plating tank. The figure below shows an overview of the galvanic generator setup.

Deposit properties. Zinc deposit, ductility, thickness uniformity and chromate receptivity in an alkaline non-cyanide bath is better than that achieved by chloride zinc baths. Unlike chloride zinc, the alkaline bath does not exhibit chipping or star-dusting when operated properly. The brighter the zinc deposit, the higher the occlusion of organics in the deposit. This makes the deposit less ductile and highly stressed. The deposit of an alkaline zinc bath is columnar while that of a chloride zinc is laminar. In many cases this makes the salt spray protection for an alkaline zinc part slightly better than that of a chloride zinc plated part.

Chloride Zinc Plating

Chloride zinc-plating processes have been available for more than 50 years and have changed considerably over this period. They have evolved from processes very sensitive to bath chemistry, temperature, current density, and so on, to processes that can be operated over a wide range of conditions. High-temperature processes are now available that enable extremely high-operating current densities for maximum throughput.

Advantages. The chloride processes offer three important advantages over the alkaline systems:

- Superior brilliance and leveling, rivaling that of nickel-chrome.

- Plating efficiencies of 95–100%.

- No carbonate formation, enabling consistent plating speed.

- Ability to plate substrates such as cast iron and, more importantly, steels hardened using any number of different methods.

- Excellent covering power can be achieved.

Disadvantages. Unfortunately, associated with these advantages are two major disadvantages: - The solutions are corrosive and therefore more expensive, due to the need for corrosion-resistant equipment.

- Throwing power of the systems is only fair, resulting in poor plate distribution. Significant thickness buildup in HCD areas, or “dogboning,” can result. Recently new systems have been evolving that can get somewhat close to the distribution we see in alkaline zinc plating baths.

Operating requirements. Suggested requirements for trouble-free operation of a chloride zinc-plating operation include monitoring and adjustment of pH as frequently as possible, at least every two hours. The bath should be analyzed once per shift or at least once a day, and cleaners and acids must be analyzed, maintained and dumped on a regular basis. Preventive maintenance can reduce production problems and minimize costs, while automatic feeders for liquid components eliminate human error and ensure consistent operating performance.

Bath makeup. No matter which bath chemistry is chosen, zinc chloride is the source of the zinc in the bath and is available as either a liquid or a solid. Zinc chloride is normally only used for bath makeup. It is important that the zinc chloride be lead-free or as lead-free as possible; the presence of lead in the bath will result in a very dull, dark and unrefined deposit and requires “dummying” the bath to remove the lead.

Potassium chloride provides solution conductivity. The untreated form of potassium chloride is preferred. Various anticake agents commonly used can be detrimental to the bath and should be avoided. Ammonium chloride serves several purposes: It provides conductivity and acts as a complexor for the zinc. Baths using ammonium chloride, in general, have a wider window of operation and are therefore easier to control, mainly due to the higher tolerance for iron contamination, up to three times that of most boric acid baths. Ammonium chloride-based baths however pose a potential waste treatment problem. If nickel or copper waste streams are not segregated, the ammonia could make removal of the nickel or copper more difficult. In some areas, the discharge of ammonia is also restricted.

Other possible bath constituents include boric acid, used only in non-ammonia systems to provide some buffering action; proprietary grain-refining and brightening additives. Acetate baths are also starting to be developed to eliminate both the use of boric acid and ammonium chloride due to REACH requirements.

Bath Treatments. Carbon packing the filters is a common treatment that is used to remove organic contaminants from the plating bath. Hydrogen peroxide (1 pint/1000 gal) and Potassium Permanganate (1-3 pounds/1000 gal) are used to treat the bath for iron and some contaminants. For rack operations, the permanganate material should only be added during downtime. Zinc dust (1-3 pounds/1000 gal) can also be used to remove some metallic contaminants such as Cd and Pb.

Process steps. Parts should be cleaned and pickled using the steps outlined for the alkaline zinc processes above. After plating, the same assortment of chromates and topcoats are available as for alkaline zinc plating. Some chromates can be more difficult to use on the fully bright chloride zinc finishes. Also, iron contamination can result in iron codeposition in high current density areas, causing discoloration of the finish. Elimination of this typically requires oxidation treatments for the iron.

Equipment and operating parameters. Tanks for chloride zinc plating can be made of polypropylene, PVC, or Koroseal lined steel tank. All should be leached before use. For barrel operations, 4–12 V at current density of 3–10 asf is recommended; for rack operations, 3–9 V at 10–40 asf. Most baths operate over a broad range of temperatures, but cooling is essential for some. Heating equipment may be needed in colder climates, as well as some newer bath technologies that require higher temperature. Any equipment coming into contact with the plating solution must be constructed of corrosion-resistant materials.

Filters are also essential, operated at one to two turnovers of plating solution per hour using polypropylene cartridges or plate style filters capable of 5–15 μm filtration. Uniform air agitation is required for rack operations. Special high-grade zinc anodes must be used, and titanium baskets with slab or ball anodes can be used, as can slabs hung from hooks. For rack processes, polypropylene or cotton material is recommended for anode bags and napped polypropylene is preferred. The bag weave should not be too tight since this could result in the bags plugging prematurely. Be sure the tops of the bags remain above the plating solution to avoid roughness.

Covering power, throwing power and efficiency. Chloride zinc deposits have excellent covering power, but poor throwing power. Deposit thickness distribution, however, is poorer than that of an alkaline zinc bath. New technology has enabled the chloride zinc systems to plate with improved distribution, better conversion coating receptivity and no star-dusting, while maintaining all the deposit properties of chloride zinc, including its laminar deposition.

Deposit properties. Chloride zinc deposits from baths that run under normal conditions are fully bright with very good leveling and acceptable ductility, uniformity and chromate receptivity. High brightener or organic levels can also make the deposit less receptive to chromates, which will result in unacceptable appearance and poor corrosion performance.

Zinc Alloy Plating

Zinc alloy plating, not including brass, did not receive meaningful recognition until the early 1980s. Since then, the range of alloys has increased and the production processes have been refined considerably. Within the last 30 years, these processes have gained widespread commercial acceptance. This is due to push from various industries looking to either replace cadmium or just increase corrosion performance beyond zinc plating’s capabilities. The automotive industry was a key driving force as car manufacturers looked to both extend warranties and reduce warranty claims.

The zinc alloy baths available today are capable of satisfying both of these needs, producing deposits that provide enhanced corrosion protection and increased lubricity, ductility and hardness.

Available processes. There are a number of commercially available zinc alloy processes. We will discuss zinc/nickel (Zn/Ni), zinc/cobalt (Zn/Co), zinc/iron (Zn/Fe), and tin/zinc (Sn/Zn).

The plating processes for the iron and cobalt alloys have additive systems similar to their non-alloy counterparts because low alloy concentrations are used in these processes. The Zn/Ni systems, however, require processes that are quite different from their non-alloy counterparts.

It has become the most popular alternative to zinc and the other alloys, due to its high corrosion protection and high tolerance to heat when plating the high-alloy variant of 12–16% nickel. This high-alloy deposit maintains a majority of its corrosion protection at elevated temperatures and provides greater wear resistance. Zn-Ni plating is 2-3 harder than Zinc.

Alkaline Zn/Ni

The alkaline zinc nickel has a higher operating cost but lower make-up cost than the acid zinc nickel, mainly because of the lack of soluble nickel anodes in the alkaline system. The alkaline Zn/Ni plating process gives good plate distribution but has very low efficiency. The zinc is replenished using a galvanic zinc generator much like that in an alkaline zinc system. The key with the alkaline zinc nickel bath is to avoid large variations of zinc concentration. As that will in turn require other bath adjustments to keep the Zn:Ni ratio consistent. The nickel source is usually a liquid nickel concentrate added by amp-hour. Filtration should be the same as an alkaline zinc bath. Cathode rod or eductors are recommended for uniformity of the plating deposit. A cooling/heating system is required to keep a consistent bath temperature. The alloy uniformity of an alkaline Zn/Ni bath is very good; typically, <1% range in Ni alloy. Waste treatment is more difficult with the alkaline system and there are also low amounts of cyanide generated.

Chloride Zn/Ni

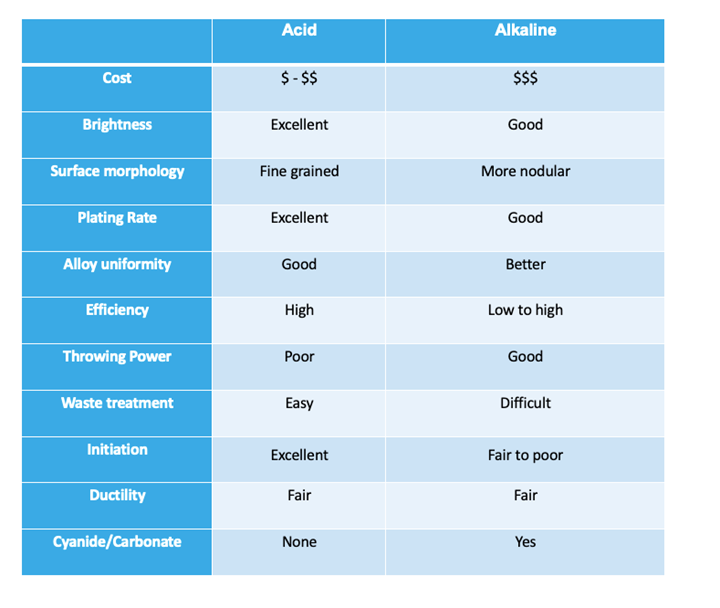

New technology has developed chloride zinc-nickel alloy systems that have alloy distribution properties almost as uniform as alkaline zinc nickel (1 – 3% Ni range). The metal replenishment of a chloride zinc nickel bath is typically done by running dual rectification with zinc and nickel on separate rectifiers. This will give you the best alloy control and lower operating cost of nickel anodes over salts. A single rectifier with zinc anodes and nickel salts fed by amp-hour can also be used in some cases. The single rectifier arrangement will lead to accelerated zinc growth, which causes unnecessary dilution of the bath. With either arrangement, the zinc anodes will need to be removed from the plating bath during downtime to avoid zinc growth. This can be done by either removing the anodes or placing in a rinse tank or empty tank, or by pumping solution out of the plating bath tank and into a holding tank. For rack applications air, eductors, or both are typically used. Filtration should be 3-5 tank turnovers per/hour with a 5-10 micron filter. Temperature control is needed to either warm or cool the bath to the recommended operating temperature. Below is a comparison chart of the Alkaline vs. Acid Zn/Ni.

Photo Credit: PAVCO

Photo Credit: PAVCO

Tin/Zinc

Tin zinc is more of a tin alloy than a zinc alloy, since the tin is present in the deposit at 70–75%, while the zinc is present at 25–30%. While the tin-zinc alloy bath is plated in acidic as well as alkaline bath formulations, the most user-friendly are generally plated at a near-neutral pH range of 6.0–7.0. The anodes used are usually 75/25 tin/zinc. Cathode agitation is mandatory. The high tin concentration in the deposit results in a higher finish cost than the other zinc alloys. The corrosion protection is similar to zinc nickel alloys. Tin zinc has good electrical properties and exceptional ductility, making it ideal for post plate fabrication. The disadvantage with the Sn/Zn deposit is that it is not suited for high temperatures.

Zinc/Cobalt

Alkaline systems for plating zinc/cobalt alloys are easy and economical to operate and produce a deposit with exceptional alloy and thickness uniformity. Like the alkaline zinc nickel alloy process, it is not unusual to actually plate a tri-alloy of zinc/cobalt/iron because of the presence of complexors. The alkaline plating process is preferred, but the chloride system can be used where it is necessary to plate hardened or cast metal parts.

Zinc/Iron

Zinc/iron deposits are currently produced using only an alkaline non-cyanide process; chloride processes to produce Zn/Fe alloys are not yet widely used commercially. The Zn/Fe baths are the most economical and easiest of the zinc alloy systems to operate. The deposit has very good corrosion resistance, ductility and weldability. Iron alloy deposits have one negative: they lose substantial corrosion protection when exposed to elevated temperatures. Thus, they are not recommended for use at temperatures greater than 200°F.

Choosing the right zinc alloy process. There are only two choices to be made. The first is the type of alloy required. The second, in the case of nickel and cobalt alloys, is whether to use an alkaline or chloride plating bath. The first choice is easy, since this is usually spelled out in the customer’s specifications. The choice of bath types can be a little more involved. There are several considerations:

- Some substrates, such as cast iron, or hardened or carbonitrided parts require chloride-type baths to plate correctly. Consistent plate initiation can be difficult using the alkaline baths on these substrates.

- Chloride baths necessitate the use of corrosion-resistant equipment. The alkaline alloy baths contain complexors that can also be corrosive to equipment. Depending on the alloy bath and the complexors used, it may be necessary to use more corrosion-resistant equipment than would be required for a normal alkaline zinc plating bath.

- In the case of nickel alloys, waste treatment modifications may be needed to handle nickel and high levels of strong complexors.

Passivates and Sealers. Because of the alloy content of the deposit, special passivate formulations are required for each of the different alloy deposits. There are currently both hexavalent and trivalent chromates available in a range of colors for most of the zinc alloys. Without a passivate conversion coating, the corrosion characteristics of the iron and cobalt alloys are not significantly different from those of pure zinc. In the case of nickel alloys, with no passivates, the onset of white salt corrosion is about the same as for pure zinc but the progression of the corrosion is slowed significantly, especially with increasing nickel content.

The passivate layers tend to concentrate the alloying constituent within the conversion layer, resulting in further enhanced protection over comparably treated zinc. Chromate formulations and parameters for alloys are significantly different from that which is used for zinc. It is also notable that the friction properties of these alloys can be much different from zinc. Tin zinc has lower µcof values, while zinc nickel has higher values. This will require modified topcoat formulations as compared to zinc in order to meet many µcof requirements specified by manufacturers.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Stripping of Plated Finishes

The processes, chemicals and equipment, plus control and troubleshooting.

-

Aluminum Anodizing

Types of anodizing, processes, equipment selection and tank construction.

-

Sizing Heating and Cooling Coils

Why is it important for you to know this?