Cause of Warping

We removed several belt guards and put them in our wheel blaster—a rotating table blaster. It removed the paint to perfection, but warped the parts so extensively that we had to hammer them back into shape.

Q: Our shop was cleaning and painting several pieces of machinery in preparation for our annual open house. We took many small machines to the back yard, where we sand blasted off the old paint and repainted the entire machines. A couple of the larger presses were wire brushed and painted in place.

My problem is, we removed several belt guards and put them in our wheel blaster—a rotating table blaster. It removed the paint to perfection, but warped the parts so extensively that we had to hammer them back into shape. Of course, they don’t look so good, but I wonder what caused them to warp when we cleaned them.

Featured Content

A: When you shot blast a metal surface, all the little “hills and valleys” that are created increase the surface area. If only one side of a metal sheet is blasted, that side will have a considerably larger surface area than the other side. The result is a curling, or warping, of the sheet. When you blasted the part in your table-top shot blaster, only one side was exposed to the blast.

It can be demonstrated that the greater the impact on one side, the greater the distortion of the metal. You did not mention the shot size in your wheel blaster, but popular sizes are around 0.33–0.46 inches in diameter, and the impact of steel shot that large hitting one side of your parts was significant. If you had turned the parts over and blasted them for the same time on each side, you would have been somewhat happier with the result.

The theory of shot peening is that the enlarged surface area on a blasted metal surface puts the surface under omni-directional compressive forces, minimizing the effect of surface stresses that result from forming, rapid cooling, or other processes.

Imagine a much sturdier piece of metal than your sheet metal parts. The part may not visibly distort. The compression forces on the surface are so great, however, that they largely overcome residual stresses and crack lines. This process is widely used in manufacturing of gears, springs, and other parts whose life is shortened by surface cracks and stresses.

Back to the distorted parts: One measure of shot peening effect is to place a metal strip in a hold-down block that ensures the strip will only be blasted on one side.

After blasting, the strip is released from the block and it will be distorted into a shallow arc shape. If the strips are standardized, then measuring the arc height of different strips run in different processes gives a relative measure of peening effectiveness in the different processes. Credit for this gaging process is given to J.O. Almen of General Motors, and the standard strips today are called, “Almen” strips.

That exercise made me feel like the guy who tells you how to build a watch when you only asked what time it is. I do find shot peening to be interesting because I learned it from John C. Straub of Wheelabrator, who, along with Almen, was one of the early researchers. I have used my limited knowledge of it in various situations. If you find it interesting you will find many good references to the process dating back to the early 1940s.

RELATED CONTENT

-

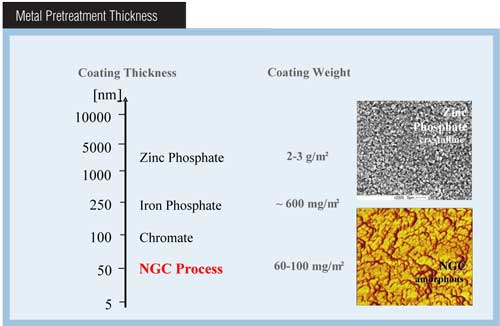

Conversion Coatings: Phosphate vs. Zirconium

Both phosphate-based and zirconium coatings have their advantages, but zirconium is fast becoming the pretreatment of choice.

-

Zinc Phosphate: Questions and Answers

Our experts share specific questions about zinc phosphate and pretreatment

-

Cleaning Limescale from Galvanized Steel

How do you clean white lime scale and rust spots on galvanize?