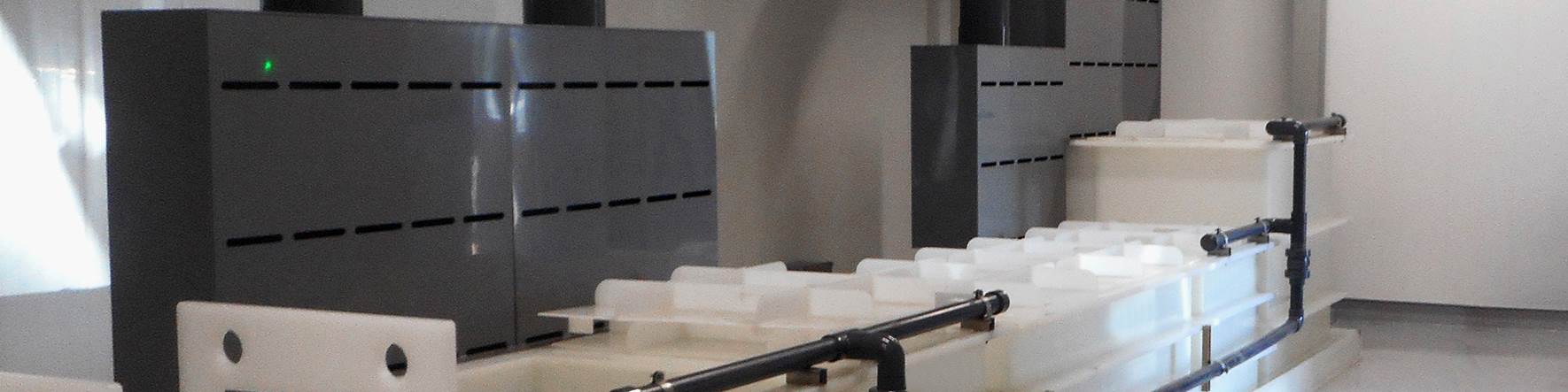

Lateral exhaust via backdraft hood with push air header opposite the hood. All photos: Tri-Mer Corporation.

Photo Credit: Tri-Mer Corporation

Open-surface tanks used for cleaning, etching, plating and other finishing tasks all require ventilation to satisfy OSHA, protect workers, protect property, and prevent malodorous or corrosive fumes from contaminating nearby areas or processes.

Exhaust ventilation can be an expensive proposition, with energy costs for temperature and humidity control among the costliest contributors. Thoughtful design, however, can not only reduce ongoing utility and “housekeeping” expenses, but minimize capital costs as well. And while the best time to consider ventilation design is before process tanks are installed, the reasons to consider a retrofit are compelling.

Featured Content

This is particularly true if chemistries have changed (and now include chrome, nickel, or cobalt), if stages have been added, if permissible exposure limits (PELs) have lower thresholds than in the past, or if parts handling equipment obstructs airflow that was once considered adequate. Ventilation also warrants a fresh look if process variables such as temperature, concentration or agitation have changed, if there has been a modification in the facility’s make-up air, or air pollution control — or if there’s an issue.

Are there visible fumes emanating from process tanks?

Strong odors? Corrosion on equipment?

All of these require a closer look. Eliminating these symptoms with improved tank ventilation will solve these issues while improving what is likely a lurking worker exposure problem, reducing the need for maintenance and repair, and lengthening the service life of susceptible components such as instrumentation and controls.

Open surface tank ventilation design fits into four broad categories: Lateral exhaust, Push-pull, Canopy hoods and Enclosing.

Lateral (“side-draft”) exhaust uses a slotted hood installed at right angles and adjacent to the work zone to pull emissions across the surface of the tank. Tank width, hazard class and the presence (or absence) of cross-drafts are factors that determine the quantity, height, and configuration of exhaust hoods. In cases where the draft distance exceeds 4 feet, lateral exhaust alone is usually insufficient.

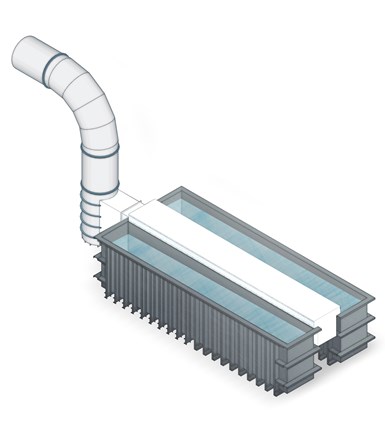

Push-pull employs a jet of air above the surface of the solution and a lateral exhaust hood, on opposite sides of the tank. A curtain of air sweeps the tank surface, forming a sheer layer on both sides of the jet. This slows the fluid in the jet and accelerates the ambient fluid. With a push-pull system, the tank walls and contents inhibit fluid entrainment on the low side of the jet, deflecting it toward the surface.

Push-pull ventilation requires significantly lower exhaust volumes versus lateral hoods, which work using exhaust alone. A push-pull system’s lower ventilation rates translate directly to smaller exhaust ducts, exhaust fans and scrubbers.

Exhausted air needs to be replaced and conditioned, and push-pull systems have an advantage in that they can be paired with smaller makeup-air units, too. Make-up air creates positive or negative pressure, depending on whether make-up air volume is more or less than the exhaust air. ANSI Z9.1 specifies that make-up air must be 90 to 110% of the exhaust air. If exhausts are hazardous, make-up air cannot exceed 100% of the exhaust.

Metal finishers are wise to maintain a slight negative air pressure, so that when an exterior door is opened, the pressure inside resists the effort. If the opposite is true, adjusting the make-up rate is required. Because make-up air is usually heated in winter, keeping it to a minimum permissible level can produce significant energy savings.

Depending on the chemistry, unheated outside air can sometimes be directed over the tank to compensate for exhaust air. Where an anodizing solution requires cooling, unheated supply air lowers the cooling requirements as well.

Push-pull is most often used with large tanks, in applications where high capture efficiency is critical, and where access or ergonomic considerations preclude using an overhead canopy.

Canopy hoods can be free-standing and open on each side, or open on just three sides. They control airflow directly in applications with sufficient control velocity, but are not appropriate where highly toxic chemicals are in use, or where thermal currents from hot processes, spot cooling or machinery motion create unavoidable cross-drafts.

Canopy hoods are rarely used in ventilating open surface tanks for several reasons: 1) hoods placed directly above process tanks can interfere with cranes/hoists and other processing equipment and 2) fumes directed vertically from the surface of the solution into an exhaust hood above are likely to travel past an operator’s breathing zone.

Enclosing hoods partially or completely surround the tank. They consist of a lateral hood and either one panel, or panels at each end. This ventilation option reduces cross-drafts by directing most of the hood airflow above the tank’s surface. Enclosing hoods become an unworkable option where operators require tank access.

Bottom side lateral (BSL) hood with push air header on anodizing process for architectural extrusions.

Exhaust equipment for finishing tanks is commonly manufactured in a thermoplastic material, providing that solution temperatures are below the threshold where an alloy option is required. The most often specified materials are PP (co-poly or homo-poly), PVC, PVDF, and CPVC. Of these, PP and PVC are the most common.

“Polyro” is stiff and rigid, with strong resistance to impact, stress fatigue, and temperature extremes. It is highly resistant to corrosion and chemical leaching, making it a worthy companion for solvents, bases and acids. It’s a wise choice for facilities prone to incidents with cranes, forklifts and other powered hazards — because it is impact resistant and can be easily welded/repaired in the field. PP also holds a load well at higher temperatures.

When ethylene is combined with the propylene during the polymerization process, the result is polypropylene copolymer. This material has increased flexibility and improved optical properties, so it’s suitable for applications where transparency and good aesthetics are an advantage.

PVDF has excellent piezoelectric properties, thermal stability, and mechanical strength. Hoods manufactured from this material have excellent resistance to acids, bases, organic solvents, oils, and fats, and exceptional insulating properties. Its continuous use temperature limit is 302°F, so it’s beneficial for finishing lines where one or more stages are held at elevated temperatures.

PVC has a high density for a plastic material, so it’s extremely strong, as well as lightweight and economical. PVC's operating peak is 140°F; CPVC can handle up to 200oF. Notably, their fittings and bonding agents are not interchangeable due to differences in ASTM specifications.

Larger fabricators also offer special flame retardant PVC, polypropylene and PVDF. PVC, for example, burns only when held in the flame. When it gets hot, it collapses and is less able to conduct air, which can feed or spread a fire.

Ventilation is a critical engineering control, one that directly affects everyone — and everything — in your shop. And whether you’re planning a new line, expanding an existing one, or just considering new chemistry, getting input from a company that offers a broad range of standard and custom tank ventilation solutions can only make you smarter — and probably save you many dollars, in the short and long run.

Tri-Mer Corp. (Owosso, MI) manufactures metal finishing systems, ventilation systems, dry and wet scrubbers, odor control systems and dust collectors. The company provides turnkey project delivery and project management worldwide. Visit tri-mer.com.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Cyanide Destruction: A New Look at an Age-Old Problem

Cyanide in mining and industrial wastewaters has been around from the beginning, including electroplating processes. This presentation reviews a number of current processes, and in particular, offers new technologies for improvement in cyanide destruction by the most common process, using sodium hypochlorite.

-

NOx Scrubbing Technology Breakthrough

This paper presents research findings and practical results that address the treatment of the problematic greenhouse gases nitrogen oxides (NOx) and sulfur dioxide (SO2).

-

Corrosion Testing of Automotive Coatings

Exposure to road salts, UV radiation, heat, moisture and chipping from kicked-up road debris can quickly degrade an automotive coating system.