What’s Next for the Aerospace NESHAP?

Will it be business as usual or are major changes in store for the aerospace industry as feds look at 40 CFR Part 63 Subpart GG, commonly referred to as the Aerospace National Emission Standard for Hazardous Air Pollutants, or NESHAP.

#masking #aerospace #pollutioncontrol

Since 1998, many aerospace manufacturing and rework facilities have been operating and maintaining records in accordance with 40 CFR Part 63 Subpart GG, commonly referred to as the Aerospace National Emission Standard for Hazardous Air Pollutants, or NESHAP.

Under the Clean Air Act (CAA), the U.S. EPA is required to continually revise the longstanding regulation. The industry is still at least a few months away from getting a glimpse at the next proposed revision—and at least three years away from having to actually implement the requirements in the forthcoming regulation. However, some reasonable projections of what the revised aerospace NESHAP rule will look like can be made based on the CAA, recent NESHAPs issued by EPA for other similar industries/source categories, information posted on the EPA website and discussions with aerospace industry trade groups and individual aerospace companies.

Featured Content

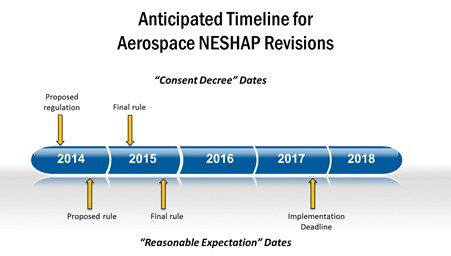

According to EPA’s Risk and Technology Review (RTR) schedule available on the Transfer Network Air Toxics website, the consent decree dates that the aerospace NESHAP is required to be revised are March 15, 2014 for the proposed rule and January 15, 2015, for the final rule. However, the EPA has historically missed statutory deadlines associated with the CAA, and these deadlines were established before the 16-day government shutdown last October.

Plan Now for Later Changes

In addition, affected aerospace facilities will be given at least a year—and probably two years—to implement any required changes called out in the final regulation. The full impact of the aerospace NESHAP is years away, but because of the potential significance of the proposed changes, some initial planning steps should be taken now.

The aerospace NESHAP was first promulgated in 1995 and most recently revised in 2000. The aerospace NESHAP as it currently stands is only applicable to major sources of HAPs, not area HAP sources. A major source of HAPs is a facility that has potential emissions of a single HAP greater than 10 tons/year or aggregate HAP emissions greater than 25 tons/year.

The most common HAPs in the aerospace industry are:

-Toluene, methanol, xylene, and methyl isobutyl ketone (used in primer and topcoat)

-Perchoroethylene (and other chlorinated compounds) used for cleaning and degreasing

-Chromium, nickel and cadmium used in primers, topcoats and plating operations.

The most significant requirements within the current aerospace NESHAP regulation are:

Primer and topcoat (organic HAP and VOC): must meet VOC and organic HAP limits on a lb/gallon basis, install an emissions control system to destroy VOC/organic HAPs, or meet limits through emissions averaging

Primer and topcoat (inorganic HAP): must install 2-stage, 3-stage or waterwash booth (depending on the installation date) to capture and reduce particulate emissions.

Other aerospace NESHAP requirements cover cleaning solvents/handwipe cleaning, flush cleaning, paint gun cleaning, paint application equipment, depainting, and chemical milling maskants, but for most of the aerospace industry, the primer and topcoat organic HAP and inorganic HAP emission limits are the most significant.

Vast Majority are OK

The vast majority of aerospace companies met the organic HAP and VOC content limits of 2.9 lb/gallon (primer) and 3.5 lb/gallon (topcoat); a smaller number of companies met these limits by emissions averaging. Very few companies installed VOC/organic HAP emissions control systems to meet aerospace NESHAP requirements for existing sources in the late ’90s.

Some aerospace companies have installed thermal oxidizers on newly constructed aircraft painting operations, but these systems were generally implemented to reduce VOC emissions below New Source Review (NSR), permitting threshold levels not to meet aerospace NESHAP requirements.

The one item that stands out in the aerospace NESHAP compared with Maximum Achievable Control Technology Standards (MACT) for other industries/source categories is the number and extent of the exemptions within the rule.

Some of the more significant exemptions are:

Specialty coatings are not required to meet VOC and organic HAP content limits. The specialty coating category can cover as much as 20 percent of a company’s total primer and topcoat usage.

The regulation does not apply to electronics and only applies to parts that are critical to structural integrity.

There is a generous “low use coating exemption” that allows an affected aerospace facility to use up to 200 gallons (max. 50 gal per formulation) of primer or topcoat that exceed the organic HAP/VOC lb/gallon limits.

By judiciously using these and other exemptions in the Aerospace NESHAP, most affected facilities are able to meet applicable requirements without needing to install costly and cumbersome VOC emission control systems, such as thermal oxidizers and carbon adsorption.

Foreshadowing EPA’s Steps

EPA has been working to revise the aerospace NESHAP as part of its RTR. One of the first steps was a data collection survey of more than 200 aerospace facilities. The second significant step was a select group of aerospace facilities were required to conduct air emissions source testing on specified operations in early 2013. EPA has published a summary of the 2011 industry questionnaires on the TTN Air Toxics website along with some foreshadowing of how the proposed regulation may be revised.

Other clues can be gathered by reviewing other industry source category NESHAPs further along in the RTR process, such as the standards for printing and publishing, shipbuilding and repair, and for miscellaneous metal parts and products.

Finally, EPA has had an ongoing dialogue with the Aerospace Industries Association (AIA) and individual aerospace companies, and has provided some guidance regarding what the proposed revisions to the aerospace NESHAP are likely to be:

The proposed revision will likely expand the list of affected sources to cover both area and major sources. This revision is consistent with the approach taken with other source categories as part of the RTR.

EPA is promoting using emission limits based on lb HAP/lb solids for coatings as opposed to a lb/gallon basis in the current regulation. This could be a more significant change than is apparent. The current primer and topcoat standards are reasonably easy to meet as the aircraft manufacturer’s approved such formulations in the late ’90s. The vast majority of compliant topcoats have VOC content right on or below the 3.5 lb/gallon limit. This fact made it easier for EPA to set the bar and allowed industry to meet the limits without emissions control systems. The organic HAP content for the same coatings will be all over the map ranging from 0.0 to 4.0 lb HAPs/lb solids. The “bar” will not likely fall as conveniently as it did in 1995. More aerospace companies will be left with non-compliant primers and topcoats where the painful and expensive option of installing emissions control systems may be the only viable alternative. In addition, depending on recordkeeping requirements, the change from a lb/gallon to lb/solids regulatory limit will require substantial paperwork and documentation for a large number of primers and topcoats. The amount of documentation and recordkeeping associated with switching from a lb/gallon to a lb/lb solid basis will be significant.

EPA has mentioned replacing the lb/gal limits with a facility-wide HAP and/or facility-wide toxicity limit in discussions with AIA. Such plans could benefit companies with limited emissions; however, this would likely be more difficult to meet than the current standards for facilities using large annual coating volumes.

Exemptions, particularly for specialty coatings, may be curtailed. All specialty coatings may have emission limits as primers and topcoats currently have.

EPA has commented that hexavalent chromium emissions, primarily from aircraft priming operations, are a major focus of the RTR and that the residual risk associated with hexavalent chromium emissions from aerospace facilities is too high. EPA appears to be focused on ratcheting down the standard for inorganic HAP emissions from priming operations. The difficulty both EPA and the industry will have is that the current standard for new sources is a three-stage filter system, which the filter manufacturer’s report as being 99% or better efficient. Given the technological limits of inorganic HAP filtration systems there are limited means to achieve further reductions.

Crystal Ball Predictions

Expect proposed revisions to the aerospace NESHAP will be issued sometime in the second half of 2014 and the revised rule will be promulgated 12-24 months after the proposal (2015 or 2016). Although the timelines are still fairly far in the future, once the proposed aerospace NESHAP is issued, aerospace facilities will need to implement compliance plans relatively quickly given the long lead times required to implement process and material modifications.

Some educated guesses regarding what the proposed regulation will look like are:

The number of affected aerospace facilities will increase from about 100 to about 250, as the revised rule will cover both “area” sources as well as “major sources.”

The “VOC/organic HAP standards” for primer and topcoat will be changed from a “lb HAP/gallon” to “lb HAP/gallon solids” requiring aerospace facilities to rework their data management systems.

Specialty coatings will no longer be exempted by the aerospace NESHAP. All coatings will have a “lb HAP/gallon solids” standard.

End-of-pipe VOC control systems, such as thermal oxidizers, the last resort compliance option that nearly every aerospace company was able to avoid in the first round, will be more difficult to avoid.

More stringent hexavalent chromium emission limits for aircraft priming operations, which may require more efficient particulate control filters, will be established.

What to Do Now?

Given that the rule has not even been proposed, aerospace companies should generally just sit tight and wait until the proposed rule is issued.

One task aerospace companies can do now is to review the ICR/RTR data, particularly related to hexavalent chromium emissions, submitted to and compiled by EPA in 2011. One company apparently overestimated hexavalent chromium emissions from a process tank by several orders of magnitude

If any discrepancies are discovered, consider submitting revised data.

Jerry Bauer is an associate engineer in the Environmental Group at Burns & McDonnell Engineering Co. He can be reached at jbauer@burnsmcd.com. Sam Sutton is an environmental engineering specialist in the Air Program Administrator at Bell Helicopter Textron Inc. He can be reached at ssutton@bh.com.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Applications Innovation Leads to Better Masking Solutions

When masking product failures are costing you money, it pays to work with an expert that can select or engineer the most efficient solution.

-

Five Principles of Lean Manufacturing from Toyota Production Systems

Fostering Sustainable business and People success through new ways of thinking

-

An Introduction to Cyclic Corrosion Testing

A more realistic way to perform salt spray tests.